“Unveiling an Ancient Mystery: How Monkeys Became the First Adventurers to Cross the Atlantic Over 30 Million Years Ago!”

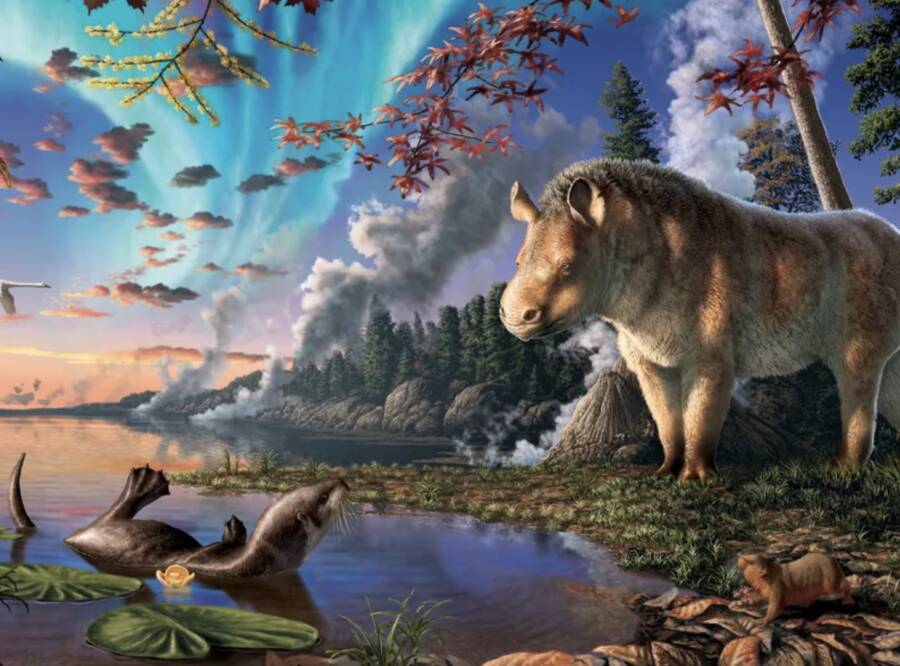

Have you ever thought about how far some creatures will go in the name of survival? Well, get ready to be amazed! Recent fossil discoveries near the Peru-Brazil border have uncovered some jaw-dropping secrets about ancient monkeys. Imagine this: 35 million years ago, a gang of now-extinct primates pulled off the seemingly impossible feat of rafting more than 900 miles across the Atlantic Ocean—yep, you heard that right! This wasn’t just a leisurely swim; they were clinging to natural rafts of vegetation, navigating their way to South America during a tropical downpour. Talk about a daring adventure! This study, published by the University of Southern California, not only showcases the resourcefulness of these little creatures but also ties into a larger story about primate evolution. So grab your explorer’s hat and join me as we dive into the fascinating world of the prehistoric primate, Ucayalipithecus perdita. Who knew survival could be so thrilling? LEARN MORE.

Fossilized evidence of a now-extinct primate species suggests prehistoric monkeys traveled more than 900 miles on natural rafts.

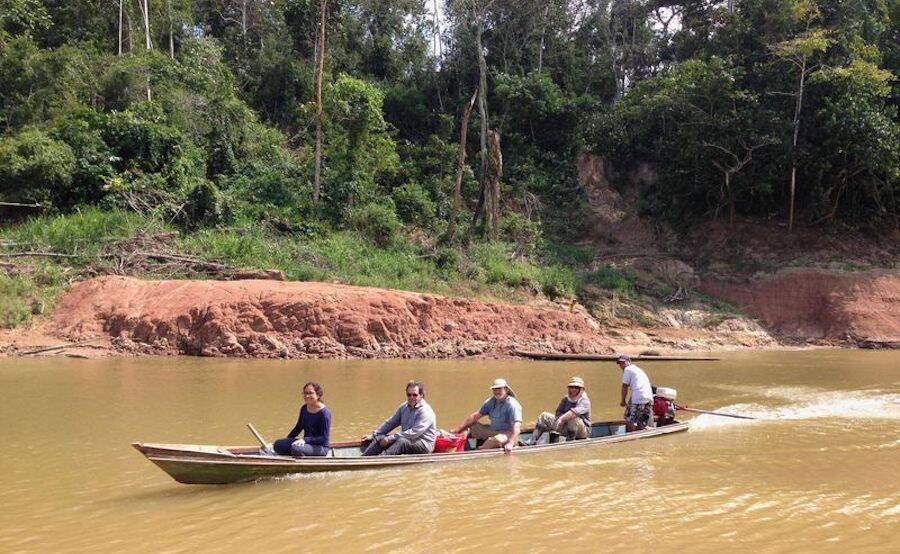

Dorien de VriesResearchers float by the 32-million-year-old fossil site behind them, on the Río Yurúa in Peru.

While modern-day monkeys are quite clever, fossils found near the border of Peru and Brazil have revealed just how smart their ancestral species really were.

A new study found a crew of now-extinct monkeys crossed the Atlantic on a natural raft, from Africa to South America — 35 million years ago.

According to Smithsonian, ancestors of today’s capuchin and woolly monkeys first arrived on the Western Hemisphere by floating on mats of vegetation and earth.

University of Southern California’s study, published in the Science journal, posits an entirely different, now extinct species, did the same.

According to CNN, experts now believe this prehistoric species of parapithecids, dubbed Ucayalipithecus perdita, made the 900-mile journey during a tropical rainstorm. Most fascinating, their diminutive stature may have been what allowed them to survive such a treacherous trip.

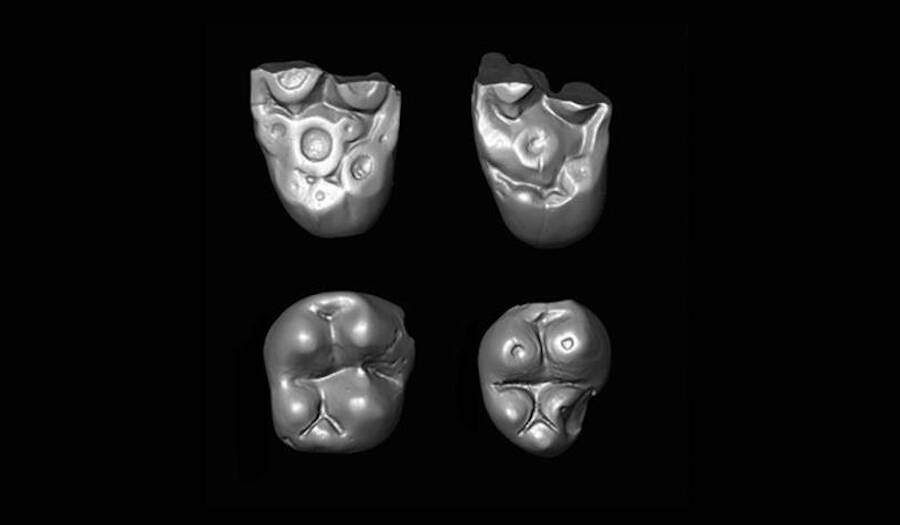

Erik SeiffertScans of the fossilized molars discovered in the Amazon.

“It would have been extremely difficult, though very small animals the size of Ucayalipithecus would be at an advantage over larger mammals in such a situation, because they would have needed less of the food and water that their raft of vegetation could have provided,” said study author Erik Seiffert.

“This is presumably why most of these overwater dispersal events that we know of in the fossil record involve very small animals,” Seiffert added.

Seiffert uncovered a set of four fossilized teeth from this second primate group on the banks of the Río Yurúa in Peru. The species in question was thought to have only lived in Africa until the paleontologist unearthed the evidence from 32-million-year-old rock.

Paleoprimatologist Ellen Miller of Wake Forest University explained that “parapithecid teeth are distinctive,” which means it’s highly unlikely that another form of monkey or animal could have grown the teeth found fossilized in Peru.

Perhaps most astonishing was the Ucayalipithecus‘s form of travel.

The “rafts” were pieces of earth that broke off from the coastline in harsh weather conditions. The resourceful little primates then boarded these small, floating islands and headed toward the New World — millions of years before that moniker came to be.

Erik SeiffertResearchers in Peru, near the border of Brazil, drying sediment in the sun on basic screens.

Researchers generally agree that there are only two other species of “immigrant” mammals that survived an Atlantic crossing, though their method of travel is still heavily debated.

New World Monkeys, or platyrrhine primates — five families of flat-nosed monkeys found in South America and Central America today — were the first. The other was a kind of rodent, dubbed caviomorphs, which are ancestors of animals such as the capybara.

As for these now-extinct primates, they made their trek during the Late Eocene, when the span between African and South American continents measured between 930 to 1,300 miles. Though that’s still quite the commute, it’s a far cry from today’s distance of 1,770 miles.

“I think everyone kind of shakes their heads at primates rafting long or even moderate distances,” said Miller.

Though it’s difficult for some to fathom, animals like lemurs and tenrecs took similar natural rafts from Africa’s mainland to Madagascar. Of course, that’s only around 260 miles — but the theory that animals have used pieces of vegetation to island- or continent-hop is very much a fact.

Seiffert explained that the Late Eocene saw a global period of cooling during which many ancient primate species across Europe, Asia, and North America were going extinct. Though there is no evidence of an alternative route to crossing the ocean, Seiffert himself had his doubts.

“I have to admit that I was much more skeptical about rafting until I saw a video of mats of vegetation floating down the Panama Canal, with trees upright and maybe even fruiting,” he said.