Uncovering Ancient Secrets: Why Did Neolithic Parents Choose Animal-Shaped Bottles for Their Babies?

Who knew that the humble baby bottle dates back thousands of years—and that these ancient nursing tools might just explain a prehistoric baby boom? Picture this: Bronze and Iron Age parents popping animal-shaped clay bottles filled with sheep, goat, or cow milk into their kiddos’ hands—like tiny mythical creatures doubling as baby toys! It’s wild to think these adorable little vessels, discovered in Bavarian infant graves, were once mistaken for feeding the elderly or infirm. But here’s the kicker—switching babies from mother’s milk to animal milk possibly unlocked a fertility secret, giving momma prehistoric women a chance to multiply their tribes faster than ever. Of course, those spouted pots were a nightmare to clean (yikes!), leading to plenty of infant illness and heartbreak. Still, this groundbreaking find by University of Bristol’s Julie Dunne unwraps an entirely new chapter on motherhood, childcare, and population growth from way back when. Ready to get the full scoop on how baby bottles may have stirred up a Neolithic population boom? LEARN MORE

Baby bottles date back thousands of years — and may help explain a prehistoric baby boom.

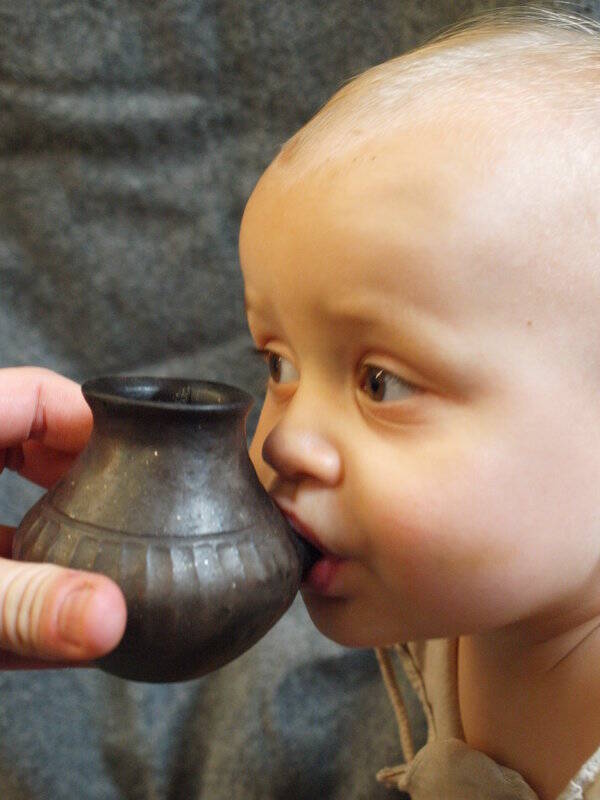

Enver-Hirsch/Wien MuseumThese ancient clay vessels were previously thought to have been used to feed the invalid or elderly.

Prehistoric parents fed their infants nonhuman milk from animal-shaped baby bottles, according to a recent study.

Archaeologists analyzed ancient spouted clay vessels discovered in the graves of Bronze and Iron Age infants in Bavaria and found traces of sheep, cow, and goat milk.

This type of pottery first appeared more than 7,000 years ago when Europeans were transitioning from hunter-gatherer to agrarian lifestyles.

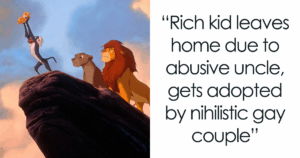

The bowls themselves date from around 2,500 to 3,200 years ago. They’re small enough for a baby to hold, with some even designed to look like mythical animals children might enjoy.

Lead author and University of Bristol archaeologist Julie Dunne believes this prehistoric find and subsequent analysis is a historic first.

“This is the first time that we’ve been able to identify the types of foods fed to prehistoric babies,” she told NPR. “I can just imagine a little prehistoric child being given one of these with milk in it and laughing. They’re just fun. They’re like a little toy as well.”

H. Seidl da Fonseca/Nature JournalWhile transitioning from the mother’s milk to that of animals allowed the mother to become more fertile again, and thus produce more children, these vessels were hard to clean and caused a lot of illness and death.

Published in the journal Nature, the study also provides one possible explanation for a Neolithic baby boom.

Scientists hadn’t “recognized that the introduction of animal milk to infants’ diets could have changed a woman’s fertility” until now, explained bioarchaeologist Siân Halcrow. This is “the first direct evidence for animal milk being contained in these bottles for feeding to babies” — and that has huge ramifications.

Katharina Rebay-SalisburyJulie Dunn and her team used chemical and isotopic analysis to find residue of milk from the ruminant family (goat, cow, and sheep). The baby boom in Neolithic Europe coincided with the period this type of clay pottery dates from.

“There’s clinical evidence that when women are breastfeeding, they have a period of infertility,” said Halcrow. “So if women aren’t constantly suckling their young, they could actually have more babies during their lifetime, and it could result in an increase in population size.”

On one hand, the transition from human to animal milk allowed for an enormous population growth. On the other, weaning babies off of human milk so early and using tiny-spouted clay pots “could have been extremely detrimental” — and led to a lot of unnecessary deaths.

“These bottles would have been so hard to clean,” said Halcrow. “Never mind them not having access to clean water in the first place. But getting into those tiny little spouts? These would have been really unsanitary to use and introduced all kinds of germs into the infant diet.”

That may explain why an estimated 35 percent of babies from that period died within a year, while only half reached adulthood.

Katharina Rebay-Salisbury/Nature JournalThe bowls were shaped like “mythical animals,” rather than realistic ones, and were small enough for a baby to hold.

Archaeologists previously speculated that this type of pottery was used to feed the infirm or the elderly — probably because women have been historical sidelined in archaeology.

“Let’s face it,” said Dunne. “Sometimes research on women tends to be a little bit marginalized compared to research on what the men in prehistoric times were doing out there….So you don’t get perhaps so much about women and motherhood and children.”

Archaeologists haven’t even started looking into women and children’s experiences in ancient societies until the last 15 or 20. But with that research comes great insights.

“Broadening our lens to include infants and children in the past is really important for a number of reasons,” said Halcrow. “They made up a high proportion of past populations. And if their health and experience is poor, that’s obviously detrimental to society’s function.”