Ancient Elixir: How Beer Became the Unexpected Key to the Wari Empire’s 500-Year Reign

Ever wonder how an empire could stay glued together for five whole centuries—without Wi-Fi, Netflix, or even a good old-fashioned coffee shop? Well, it turns out the secret sauce for the ancient Wari civilization wasn’t some high-tech gadget or even a killer army. Nope. It was beer. Lots of beer. The Wari, those brainiacs who gave rise to the Incas high up in the Peruvian Andes, kept their social and political world bubbling along with a constant flow of chicha—a sour, frothy brew that brought rival tribes together, one festival at a time. Imagine 200 local leaders clinking three-foot-tall beer vessels, adorned with gods and legends, pledging loyalty over rounds of this potent potion. Talk about politics on tap! And since this chicha was as fresh as your morning latte (lasting just a week), people had every reason to gather ‘round fast. So, could it be that the key to one of ancient South America’s longest-lasting empires was just… beer, banter, and boisterous parties? Let’s dive into how these spirited gatherings brewed not just beer, but a 500-year political marvel. LEARN MORE

Researchers believe that a focus on brewing, sharing, and hosting beer-centric festivities was integral to the Wari’s social stability for 500 years.

Wikimedia Commons“Chicha,” the preferred beverage of the ancient Wari culture, is still served today in Colombia.

A new study in which researchers sought to observe how drinking helped to maintain political relations in ancient societies posits that the culture which eventually gave rise to the Incas was able to survive for 500 years because of a constant flow of beer between them and rival tribes.

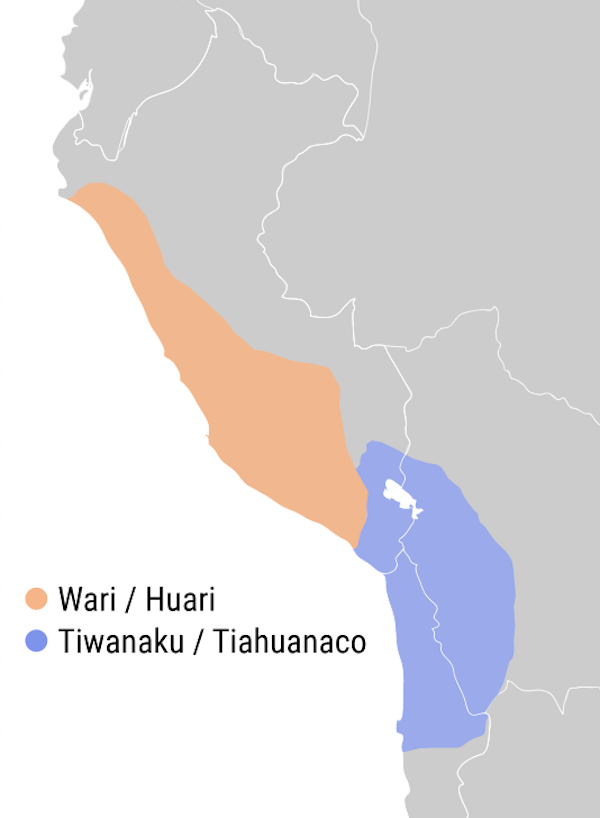

The pre-Incan civilization known as the Wari empire emerged in the highlands of Ayacucho in Central Peru around 600 A.D. The Waris are believed to have been the very first centrally governed state to appear in the Andes.

Until 1100 A.D., the Wari people were assembled in varying tribes that routinely socialized with rival groups, particularly from the Bolivian Tiwanaku people which vastly influenced their culture.

According to the results published in Sustainability, scientists were able to assess the kind of molecules and atomic remnants once housed within Wari ceramic vessels discovered almost 20 years ago using “archaometric” laser methods, which revealed that these ancient Peruvians routinely brewed beer and regularly engaged in socially lubricated gatherings.

Wikimedia CommonsA map of South America’s Wari and Tiwanaku empires, depicting their expansion and area of influence.

Business Standard reported that it was nearly 20 years ago that Ryan Williams — lead author of the study and associate curator at the Field Museum — and his team uncovered evidence of an ancient brewery in Cerro Baúl in the southern mountainous parts of Peru.

As technology has come quite a long way since then, the team has only recently managed to extrapolate further invaluable data from their previous archaeological findings. “We were able to apply new technologies to capture information about how ancient beer was produced and what it meant to societies in the past,” Williams said. “This study helps us understand how beer fed the creation of complex political organizations.”

The Wari brewed a sour beverage called “chicha,” and since it only lasted for a week after its brew date, the people had to come to Cerro Baúl to partake as soon as possible.

“It was like a microbrewery in some respects,” said Williams. “It was a production house, but the brewhouses and taverns would have been right next door.”

Wikimedia CommonsChicha is still made by South America’s indigenous population today and is sold as an alcoholic beverage in bars and restaurants.

Regular festivals and beer-laden social gatherings were an ingrained part of Wari society. The study suggests that up to 200 local political figures would attend these events at which chicha was consumed from three-foot-tall vessels adorned with Wari gods and leaders.

“People would have come into this site, in these festive moments, in order to recreate and reaffirm their affiliation with these Wari lords and maybe bring tribute and pledge loyalty to the Wari state,” said Williams.

The fact that chicha had such a short half-life and wasn’t shipped away was likely a vital factor in bringing the people to one, centralized locale. With the satisfaction of alcohol consumption and communal interaction, the study’s central claim that this brewing practice was beneficial for long-standing stability isn’t entirely unfounded.

By analyzing the ceramic vessels themselves, Williams and his team also discovered how chicha was brewed in the days of yore.

Scientists shot a laser at a shard of a beer vessel, which safely removed a small bit of material without jeopardizing the entire item, and then heated said material to dust in order to separate the molecules of which it consisted. This revealed what atomic elements, and how many, comprised the sample.

In order to confirm whether or not chicha ingredients could be transferred into these ceramic vessels in the first place, however, the team had to recreate the brewing process itself. Donna Nash, a professor at the University of North Carolina Greensboro, spearheaded this part of the study.