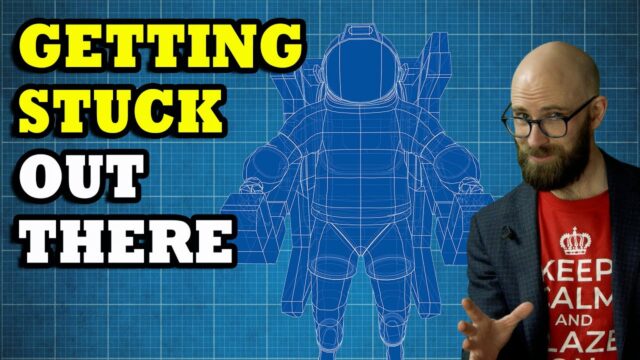

“Defying Gravity: The Untold Secrets Behind the Space Jetpack Revolution”

On February 7, 1984, NASA astronaut Bruce McCandless II took an exhilarating leap into the unknown, floating aboard the Space Shuttle Challenger, not just tethered to his spacecraft but completely free—thanks to the ingenious Manned Maneuvering Unit (MMU) strapped to his back. Imagine the thrill of zipping through space as if you were the star of a sci-fi blockbuster! McCandless touched the joysticks, and jets of nitrogen gas propelled him into the void. In that daring moment, he became the first human to experience the sheer liberation of flying untethered in space—how cool is that?

But let’s face it: while jetpacks are the stuff of our wildest dreams and beloved by characters in shows like *Star Wars*, it kind of makes you wonder why astronauts today still have to stick to those umbilicals. I mean, what’s the point of all that training if they can’t zoom around like superheroes? As we delve into this fascinating history of space jetpacks, we’ll uncover not only the groundbreaking moments that led to McCandless’s flight but also why these marvelous contraptions faded from the cosmic spotlight. So, buckle up, and let’s jet off into the quirky and thrilling tale of the space jetpack!

On February 7, 1984, 370 kilometres above the earth, NASA astronaut Bruce McCandless II floated into the payload bay of the Space Shuttle Challenger and prepared to make history. Strapped to his back was a bulky device resembling a futuristic chair, known as the Manned Maneuvering Unit or MMU. As he gently touched the joysticks on the twin armrests, jets of nitrogen gas propelled him out of the payload bay and out into the void. In that moment, McCandless achieved the ultimate dream of every astronaut, becoming the first human in history to fly freely and untethered outside the safety of a spacecraft. Rocket packs are a staple of science fiction, allowing heroes and villains alike to zip around freely both in space and on the ground – indeed, where would the Mandalorians in Star Wars be without them? Today, however, Extravehicular Activities or EVAs – AKA “spacewalks” – are always performed with the astronauts safely tethered to their spacecraft. But wouldn’t a space jetpack give them greater mobility? Why aren’t devices like the MMU used anymore? Well, strap into your chair and let’s dive into it all shall we? This is the long and fascinating history of the space jet pack.

On February 7, 1984, 370 kilometres above the earth, NASA astronaut Bruce McCandless II floated into the payload bay of the Space Shuttle Challenger and prepared to make history. Strapped to his back was a bulky device resembling a futuristic chair, known as the Manned Maneuvering Unit or MMU. As he gently touched the joysticks on the twin armrests, jets of nitrogen gas propelled him out of the payload bay and out into the void. In that moment, McCandless achieved the ultimate dream of every astronaut, becoming the first human in history to fly freely and untethered outside the safety of a spacecraft. Rocket packs are a staple of science fiction, allowing heroes and villains alike to zip around freely both in space and on the ground – indeed, where would the Mandalorians in Star Wars be without them? Today, however, Extravehicular Activities or EVAs – AKA “spacewalks” – are always performed with the astronauts safely tethered to their spacecraft. But wouldn’t a space jetpack give them greater mobility? Why aren’t devices like the MMU used anymore? Well, strap into your chair and let’s dive into it all shall we? This is the long and fascinating history of the space jet pack.

Even before the space age began, engineers knew that future astronauts would need some way of maneuvering outside their spacecraft to carry out construction work, repairs, and other tasks. On March 9, 1955, the television series Disneyland aired an episode titled Man in Space, featuring former German rocket scientists – and possible war criminals – Wernher von Braun and Heinz Haber presenting their predictions about the future of astronautics. Among the hypothetical hardware presented was the so-called “bottle suit”, a rigid, one-man spacecraft with maneuvering thrusters and robotic arms that could be manipulated from the inside. Such devices, however, proved too heavy and complicated for early space missions, and the first astronauts headed into the void far less well-equipped. Indeed, when Soviet cosmonaut Alexei Leonov became the first person to perform an extravehicular activity or “spacewalk” on March 18, 1965, he had no thrusters of any kind and had to tug on his umbilical hose or use handholds on the outside of the Voskhod II spacecraft to move around. While Leonov initially had few difficulties maneuvering himself, his Berkut space suit ballooned in the vacuum of space, making it impossible for him to fit back in the airlock. Whoopsadoodle… More on his harrowing tale in the Bonus Facts in a bit.

Meanwhile, across the Atlantic, American companies were coming up with a host of weird and wonderful devices to improve the mobility of spacewalking astronauts. Among the strangest was the “space sled” proposed by the Marquardt Corporation of Van Nuys, California. Resembling nothing so much as a space motorcycle, the contraption featured a seat, headrest, handlebars, and an array of nitrogen gas thrusters to allow an astronaut to maneuver untethered outside his spacecraft. However, for the first American spacewalk on June 3, 1965, Gemini 4 astronaut Ed White used the far smaller Hand-held Maneuvering Unit or HHMU. Nicknamed the “zip gun”, the device comprised two small cylinders of compressed nitrogen connected to a crossbar with three nozzles: two on the ends of the boom, angled backwards to propel the astronaut forward; and one in the centre facing forward to provide a braking force. It also included a handgrip with a large trigger, a mount for a camera, and a wrist strap and tether to prevent the unit from drifting away. White found the HHMU easy and enjoyable to use, though he soon ran out of propellant and had to resort to tugging on his umbilical as Leonov had. White’s crewmate James McDivitt, however, remembered the HHMU being “hopeless”, since it needed to be held very close to the astronaut’s centre of gravity or else it would send him tumbling head over heels.

Nonetheless, NASA continued to tinker with the HHMU, changing the propellant to Freon 14 fed from a larger tank on the astronaut’s back. This version was to be used by astronaut David Scott during the Gemini 8 mission in March 1966, but his EVA had to be abandoned when the spacecraft suddenly snapped into a nearly-lethal roll, forcing fellow astronaut Neil Armstrong to perform one of the most legendary feats of piloting in spaceflight history.

Meanwhile, the U.S. Air Force, still trying to maintain a presence in the increasingly civilian-dominated realm of manned spaceflight, was planning to launch its own space station, the Manned Orbiting Laboratory or MOL. As part of this project, the Air Force developed the first true “space jetpack”, known as the Astronaut Maneuvering Unit or AMU. Worn on the astronaut’s back and controlled using two joysticks mounted on fold-down armrests, the AMU was powered by concentrated hydrogen peroxide, which was passed over a catalyst to decompose it into high-temperature oxygen and steam. This allowed the AMU to reach a maximum speed of up to 76 metres per second. Because the exhaust coming out of the nozzles was extremely hot, the astronaut had to wear special trousers made of woven chromium alloy cloth to protect the spacesuit beneath. The AMU was scheduled to be tested during the Gemini 9A mission, launched on June 3, 1966. Astronaut Eugene Cernan – later the last man to walk on the moon – was to exit the spacecraft, make his way to the rear compartment where the AMU was stored, strap on the backpack, and use it to fly around the capsule. But almost immediately, the EVA started going very, very wrong. With no hand or footholds installed on the spacecraft exterior, Cernan found it extremely difficult to reach the rear of the spacecraft and strap on the AMU. This, combined with a spacesuit he later described as having “all the flexibility of a rusty suit of armour,” caused Cernan’s heart rate and body temperature to shoot up. This, in turn, overwhelmed his spacesuit’s air cooling system, causing his visor to completely fog up – which, given that he was hurtling around the earth outside the safety of his spacecraft, was a little bit of a problem. Though Cernan managed to gain some visibility by rubbing away the condensation with the tip of his nose, he was too exhausted to carry on and Mission Control decided to scrub the rest of the EVA. But Cernan’s troubles were not over yet, for his suit, like Alexei Leonov’s, had ballooned significantly, and bending down to allow the spacecraft hatch to seal was an excruciating experience.

As a result of Cernan’s harrowing experience, subsequent Gemini capsules were fitted with numerous hand and footholds, while the A7L space suits used on the Apollo missions used more effective liquid cooling systems. As for the AMU, another trial was planned for the Gemini 12 mission, but this was scrapped at the last minute. The Manned Orbiting Laboratory was cancelled in 1969 before a manned mission could be flown, and with it went the original version of the AMU. Instead, during the Gemini 10 mission in July 1966, astronaut Michael Collins used an upgraded version of the HHMU “zip gun” whose nitrogen propellant was supplied through the astronaut’s umbilical. The device was also carried aboard Gemini 11 in September 1966, but astronaut Richard Gordon cut his EVA short due to fatigue before he could use it.

As the Apollo missions had no need for such equipment, it would not be until the Skylab space station program in the mid-1970s that work on astronaut maneuvering units resumed, the work being spearheaded by NASA engineer Charles Whitsett. One of Whitsett;s designs, the nitrogen-fuelled Experiment M-509, was launched aboard Skylab on May 14, 1973, but a failure during launch caused part of the station’s micrometeorite and sun shield and one of its solar panels to be torn off. While the Skylab 2 crew, launched on May 25, managed to repair the station and keep it operational, NASA forbade the astronauts from using M-509 as it feared the wildly fluctuating temperatures aboard the crippled station could have damaged the backpack’s nickel-cadmium batteries. The Skylab 3 and 4 crews, however, would perform extensive tests of upgraded versions known as the Automatically Stabilized Maneuvering Unit or ASMU and the Foot Controlled Maneuvering Unit or FCMU. But while the astronauts collectively accumulated 14 hours flying time on both models, they were only tested inside the spacious interior of the Skylab station; actual EVAs were performed using umbilicals for fear of damaging the station’s delicate solar panel arrays and astronomical instruments.

It was not until the Space Shuttle Program got underway in the 1980s that an astronaut “jet pack” would finally be flown in open space. This was the Manned Maneuvering Unit or MMU, a direct descendant of the Skylab-era ASMU. Developed by Martin Marietta of Denver, Colorado, the MMU measured 127cm high, 83 cm wide, and 69 centimetres deep and weighed 148 kilograms. Designed to fit over the

Primary Life Support System or PLSS backpack of the Extravehicular Mobility Unit – the standard shuttle EVA suit – the unit held 12 kilograms of compressed nitrogen in two tanks – enough to last up to 6 hours and propel the astronaut to a maximum velocity of 25 metres per second. The propellant gas was vented through an array of 24 nozzles which allowed the astronaut to translate and roll themselves in any direction. These in turn were controlled by a pair of joysticks mounted on hold-down armrests, which automatically deployed when the astronaut backed themselves into the MMU frame. The unit also featured an automatic station-keeping system to free the astronaut’s hands while performing work. Many roles were envisioned for the MMU, including capturing and repairing satellites, building and maintaining space stations, and inspecting the tiles of the space shuttle’s Thermal Protection System for damage.

The person most associated with the development and testing of the MMU is astronaut Bruce McCandless II. Originally a flight instructor in the U.S. Navy, McCandless was recruited into NASA in 1966 as part of Astronaut Group 5. Like many of his fellow recruits, McCandless’s lack of test pilot experience placed him at the rear of the prime flight rotation; he thus spent the first 18 years of his NASA career on the ground, serving as a Capsule Communicator or CAPCOM for Apollo 11 and 14 and Skylab 3 and 4, and backup pilot for Skylab 2. It was during the latter mission that he became interested in astronaut maneuvering units, and as the Skylab program gave way to the Space Shuttle, he chose to become mission specialist for the then in-development MMU – a position that would guarantee him a spaceflight.

The $26.7 million contract for the MMU was awarded to Martin Marietta in February 1980, with the first two flight test units arriving at the Johnson Space Centre in Houston, Texas, in September 1983. The year before, NASA announced that the MMU would be used to repair the Solar Max scientific satellite, which had been launched in February 1980 but suffered a failure in its attitude control system requiring it to be placed in standby mode. But before this mission could take place, the MMU had to be thoroughly tested in orbit. These tests would be performed by astronauts Bruce McCandless and and Bob Stewart aboard STS-41B, scheduled for launch in February 1984. According to the official press kit for the mission, the mission would be a conservative one, with the astronauts piloting their MMUs out to 50 then 100 metres from the shuttle before returning. As mission commander Vance Brand joked:

“We didn’t want to come back and face their wives if we lost either one of them up there!”

In preparation for the mission, McCandless and Stewart trained on Martin Marietta’s Space Operations Simulator, a giant rotating gimbal mounted on a rolling base that allowed astronauts to “fly” a mockup MMU around a large warehouse. As McCandless later recalled:

“It was quite effective, and could accommodate a fully-suited astronaut and reasonable sized mockups of “target” objects, such as the underside of the orbiter for TPS repairs. It also had the capability for introducing malfunctions for training purposes.”

Finally, on February 3, 1984, the Space Shuttle Challenger blasted off from Kennedy Space Centre and climbed into orbit. Crewed by Commander Vance Brand, Pilot Robert Gibson, and mission specialists Bruce McCandless, Bob Steward, and Ronald McNair, the shuttle carried in its payload bay two communications satellites, the American Westar 6 and Indonesian Palapa B2, as well as the two MMU prototypes, playfully nicknamed “Buck” and “Flash” after 1930s pulp space adventure heroes Buck Rogers and Flash Gordon. Westar 6 was deployed eight hours after reaching orbit, and Palapa B2 four days later. However, failures in their rocket boosters placed both satellites into lower, operationally useless orbits, necessitating another mission to retrieve and re-launch them.

Then, on February 7, the time came for Bruce McCandless and Bob Stewart to make spaceflight history. After lowering the cabin pressure and pre-breathing oxygen to flush nitrogen from their bodies and avoid “the bends”, the astronauts donned their EMUs and made their way through the airlock to the cargo bay. While McCandless inspected his MMU, Stewart hooked his feet into the Manipulator Foot Restraint or MFR on the end of the Shuttle’s robotic Remote Manipulator System or RMS – AKA the Canadarm. Once satisfied with his equipment, McCandless backed himself into the MMU frame and detached himself from the payload bay bulkhead. In that moment, he became the first astronaut to fly untethered outside a spacecraft. Reflecting on this momentous occasion, McCandless – who, you’ll recall, was CAPCOM during Apollo 11, quipped:

“That may have been one small step for Neil, but it’s a heck of a big leap for me.”

Working slowly and methodically, McCandless translated and rotated the MMU through all six degrees of freedom before flying down the length of the payload bay. Finding the MMU highly responsive and intuitive to use, McCandless was at last ready to head out into the unknown. Though momentarily hesitant – who wouldn’t be? – McCandless immediately reminded himself:

“I knew the laws of physics hadn’t been repealed recently.”

After tentatively flying out to 45 metres and immediately returning, he flew out to 100 metres from the shuttle – a free flight EVA record that still stands to this day. The mission also contributed massively to the iconography of NASA and manned spaceflight in general: one photo taken of McCandless during his historic EVA, nicknamed “Backpacking”, is one of NASA’s most-requested images, and perhaps the second most famous depiction of an astronaut after the iconic photo of Buzz Aldrin on the lunar surface during the Apollo 11 mission.

Yet, as is often the case with such missions, McCandless remembered the event as rather less profound than expected:

“I was grossly over-trained. I was just anxious to get out there and fly. I felt very comfortable … It got so cold my teeth were chattering and I was shivering, but that was a very minor thing. … I’d been told of the quiet vacuum you experience in space, but with three radio links saying, ‘How’s your oxygen holding out?’, ‘Stay away from the engines!’ and ‘When’s my turn?’, it wasn’t that peaceful … It was a wonderful feeling, a mix of personal elation and professional pride: it had taken many years to get to that point.”

Returning to the shuttle, McCandless flew past the flight deck, where he asked Commander Brand if he needed his windows cleaned. Brand declined the offer. McCandless then returned to the cargo bay, stored his MMU, and switched places with Stewart on the Canadarm. While Stewart performed his own tests of the MMU, flying out to 91 metres from the shuttle, mission specialist Ronald McNair maneuvered McCandless on the end of the Canadarm to a piece of equipment known as the Shuttle Pallet Satellite or SPAS-01A, where he practiced various procedures that would be necessary for the upcoming Solar Max repair mission. Stewart’s evaluation of the MMU was just as enthusiastic as McCandless’s, with the astronaut later declaring:

“I decided that this was the easiest thing I had ever flown. The only way you could make it easier would be to wire it directly to your brain.”

Upon completing his test flight, Stewart returned to the cargo bay, clipped a docking module called the Trunnion Pin Attachment Device or TPAD to the front of his MMU, and used it to practice docking with the SPAS. The astronauts then ended their EVA after 5 hours and 55 minutes.

Two days later, McCandless and Steward headed once more into the void on a 6-hour, 17 minute spacewalk during which they practiced docking with the SPAS, tested the MMU’s automatic attitude-keeping system, and simulated the transfer of hydrazine fuel from the shuttle’s reaction control system or RCS. During the EVA, the astronauts received a phone call from President Ronald Reagan, who congratulated them on their historic mission two days before. Another highlight of the mission took place the following day when McNair, an accomplished saxophonist, became the first astronaut to play the instrument in orbit. This proved more challenging than expected, as microgravity caused spit to float inside the instrument, producing a bubbling sound, while the dry air and low atmospheric pressure in the shuttle cabin wreaked havoc on the valves and reeds. Nonetheless, it was a giant leap for Jazz-kind. That same day, the Soviet Union launched three cosmonauts to the Salyut-7 space station, raising the number of people in space to a record-setting eight and prompting one astronaut to quip: “It’s really getting to be populated up here.”

Their mission objectives complete, the crew of STS-41B returned to earth on February 11, 1984, becoming the first shuttle mission to land on the recently-completed runway at Kennedy Space Centre – previous missions had landed at Edwards Air Force Base in California. The next use of the MMU came in April 1984 during STS-41C, whose primary mission was to repair the malfunctioning Solar Max satellite. On April 9, after Commander Robert Crippen maneuvered the Space Shuttle Challenger to within 60 metres of the satellite, astronauts James van Hoften and George Nelson donned their MMUs and flew out to try and capture it. Unfortunately, all attempts to clamp onto it with the TPAD failed – a problem eventually traced to a badly-machined component on the device’s docking probe. Then, Nelson attempted to grab one of the solar arrays by hand, causing the satellite to start tumbling wildly and forcing the EVA to be abandoned. The next day, controllers on the ground managed to get Solar Max back under control, whereupon Mission Specialist Terry Hart succeeded in using the Canadarm to capture the satellite and bring it into the Payload Bay, where Nelson and van Hoften succeeded in repairing it over the course of two EVAs. Solar Max was released back into orbit the following day and remained in orbit for another 5 years, reentering the atmosphere and burning up over the Indian Ocean on December 2, 1989. STS-41C safely returned to earth on April 13, 1984.

The third shuttle mission to deploy the MMU was STS-51-A, flown by the Space Shuttle Discovery. Launched on November 8, 1984, the mission’s primary objective was to recover the Westar 6 and Palapa B2 communications satellites unsuccessfully launched by tSTS-41B. The mission also deployed two more communications satellites: the Canadian Anik D2 and the American Syncom IV-1.

The first satellite to be recovered was Palapa B2, which the shuttle rendezvoused with on November 13. Flying the MMU, Mission Specialist Joseph Allen inserted a unit called the Apogee Capture Device or “Stinger” into the satellite’s apogee motor nozzle, which fellow specialist Dale Gardner hooked onto using the Canadarm. Unfortunately, this procedure proved more difficult than anticipated, and it took two hours of Allen manually maneuvering the Stinger into the Canadarm docking adapter before the capture was at last achieved. The capture of Westar 6, which took place the following day, proved far less difficult. Both satellites were returned to earth intact, with the refurbished Palapa B2P being re-launched in March 1987 and Westar 6 – sold to Hong Kong and renamed AsiaSat 1 – on April 1990.

As it turned out, STS-51A would be the MMU’s final mission. Following the Challenger disaster on January 28, 1986, a review of NASA’s safety policies concluded that free-flight EVAs using the MMU were unnecessarily risky. Furthermore, in the wake of the disaster, NASA discontinued its policy of using the space shuttle to carry out military and private satellite launches and repairs – one of the primary tasks for which the MMU was designed. Finally, the three MMU missions had revealed that the majority of these tasks could be just as capably performed using the much safer and more versatile Canadarm. As a result, the MMU was retired from service, and three space-flown examples are now on public display at the Smithsonian’s Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Centre in Chantilly, Virginia, the U.S. Space & Rocket Center in Huntsville, Alabama, and the Johnson Space Center in Houston, Texas. Despite its short service life, the MMU remains a significant milestone in aerospace engineering, winning manufacturer Martin Marietta the National Aeronautic Association’s prestigious Collier Trophy in 1984.

The Soviet Union also developed its own astronaut maneuvering unit known as the SPK for use aboard the space station Mir. Though roughly similar to the MMU, the SPK used oxygen as its propellant and was always flown tethered to the station. Like NASA, the Soviets quickly realized that the SPK’s role could be more easily carried out using the Strela crane – the Russian equivalent of the Canadarm; consequently, the SPK was only tested during two EVAs in 1990 before being retired.

Today, the spirit of the MMU lives on in the Simplified Aid for EVA Rescue or SAFER, designed to allow astronauts to fly back to the International Space Station should they become detached from the Canadarm or their safety tethers. Developed by former astronauts Joseph Kerwin, Paul Cottingham, and Ted Christian working with Lockheed Martin, SAFER was first tested in orbit by astronauts Marc Lee and Carl Meader during the 1994 STS-64 mission. Effectively a miniaturized version of the MMU, SAFER attaches to the bottom of a regular EMU’s PLSS backpack and contains 1.4kg of compressed nitrogen – just enough to reach a maximum velocity of 3 metres per second and return the astronaut to safety. Today, SAFER is standard equipment aboard the ISS, where EVAs are always performed with the astronauts safely tethered to the station. While it may not be as glamorous as Buck Rogers or Star Wars, as any astronaut can tell you, it’s a heck of a lot better than being lost in space.

Bonus Fact:

Going back to Alexei Leonov being the first man to space walk and getting stuck out there, for a brief background, Leonov was one of the twenty Soviet Air Force Pilots to be chosen for the first cosmonaut group. Originally, his historic walk was supposed to have happened on the Vostok 11 mission, but as that was cancelled; it was later performed on the Voskhod 2 instead. After eighteen long months of training for the event, Leonov was ready to become the first person to walk in space.