“Hidden for Millennia: Scientists Unveil Secrets of a Lost Roman City with Revolutionary Laser Technology!”

What happens when a vibrant Roman city is left to the whims of time, buried beneath layers of earth and history? The tale of Falerii Novi, which vanished from modern memory in 700 A.D. and lay dormant, brings to mind an ancient version of that classic joke—”it’s like they just checked out and never left a forwarding address!” But fret not, dear reader, for thanks to groundbreaking advancements in ground-penetrating radar technology, archaeologists are peeling back the layers of this buried past. They’ve effectively rediscovered a thriving hub filled with theaters, shops, and unknown monuments that once buzzed with life. Join me as we explore how the meticulous mapping of Falerii Novi could revolutionize our understanding of Roman urban life… and possibly reveal what future civilizations might find when they dig into our own not-so-deep histories. This isn’t just ancient history—it’s a treasure map leading us to answers about how locals interacted with the immense power of Rome. If only those ancient citizens had left us a note! LEARN MORE

The city of Falerii Novi was abandoned in 700 A.D. and has been buried ever since.

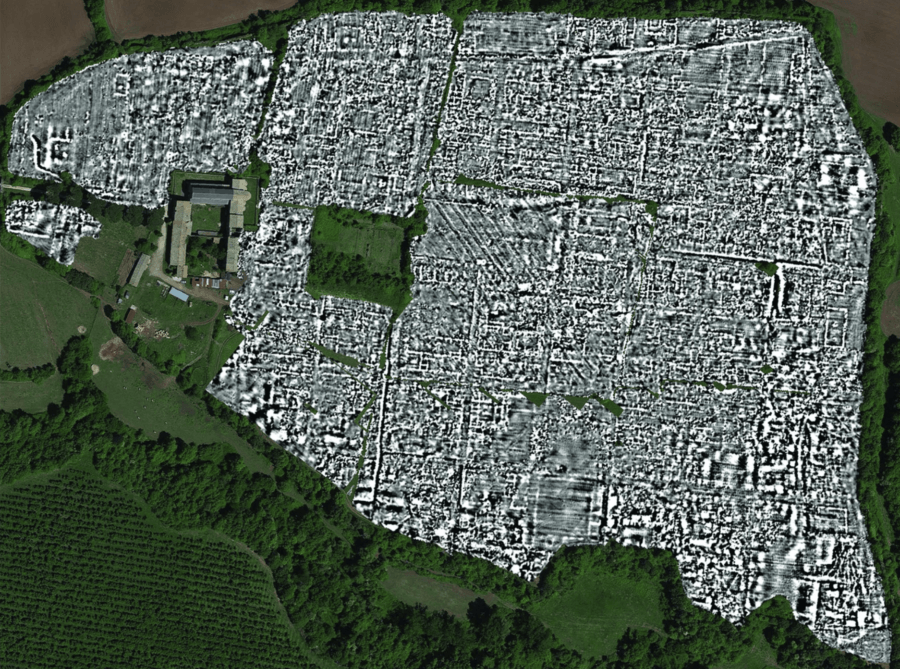

Verdonck et al., 2020/AntiquityFalerii Novi was populated by around 3,000 people and contained a theater, shops, and monuments.

For the first time in history, archaeologists have mapped an entire ancient Roman city using ground-penetrating radar. According to The Guardian, the buried town of Falerii Novi contained a bathhouse, theater, several temples and shops, and a large monument of a kind experts have never seen before.

Once a proud, 75-acre outpost 31 miles north of Rome, Falerii Novi was built and occupied in 241 B.C. and abandoned in 700 A.D. Though it’s been thoroughly buried over the course of time, new technology has allowed experts to see through layers of ground and map the town in detail without digging.

According to CNN, the uncovered public monument baffling experts is only one example of how this new approach could change the field of archaeology. Published in the Antiquity journal, the findings indicate this could merely be the first — in a long line of ancient cities — to be explored this way.

“The astonishing level of detail which we have achieved at Falerii Novi, and the surprising features that [ground-penetrating radar] has revealed, suggest that this type of survey could transform the way archaeologists investigate urban sites, as total entities,” said study author Martin Millett, who teaches classical archaeology at the University of Cambridge.

Verdonck et al., 2020/AntiquityResearchers have yet to analyze all the data they’ve captured — which they imagine will take up to a year.

A joint effort on behalf of the University of Cambridge and the University of Ghent, the scans uncovered a route along the outskirts of the city which Millett believes was likely used as a religious processional way.

For him, no kind of settlement is more informative than urban hubs like this when studying Ancient Rome.

“If you’re interested in the Roman Empire, cities are absolutely critical because that is how the Roman Empire worked — it ran everything through local cities,” he said. “Most of what we’ve got, apart from in sites like Pompeii, are little bits.”

“You can dig a trench and get little insights, but it’s very difficult to see how they work as a whole. What remote sensing does is enable us to look at very large, complete sites, and to see in detail the structure of those cities without digging a hole.”

Verdonck et al., 2020/AntiquityThe GPR took readings every five inches, and was towed by a quad bike.

Falerii Novi is around half as large as Pompeii. Fortunately, it hasn’t been built over, which made the scanning process rather easy. To do so, researchers simply towed a series of antennae over the ground by riding a quad bike across the site. This array of antennae took readings every five inches.

The approach is fairly similar to standard radar technology and essentially sends radio waves into the ground. By hitting and bouncing off objects and their surfaces, their echoes reveal how deep certain surfaces are compared to others — and thereby create a detailed, three-dimensional picture.

The water system’s construction revealed it was built before the structures atop were — instead of running along the grid of streets. This foresight in planning was enacted “in a way that’s familiar today, but not expected, I think, in the third century B.C.,” explained Millett.

The public monument, meanwhile, was nearly 200 feet long and lined with colonnades. It contained two smaller structures with niches allowing for fountains and statues. Millett was naturally stunned at the find, and claimed “no one I’ve yet shown it to yet knows what it is.”

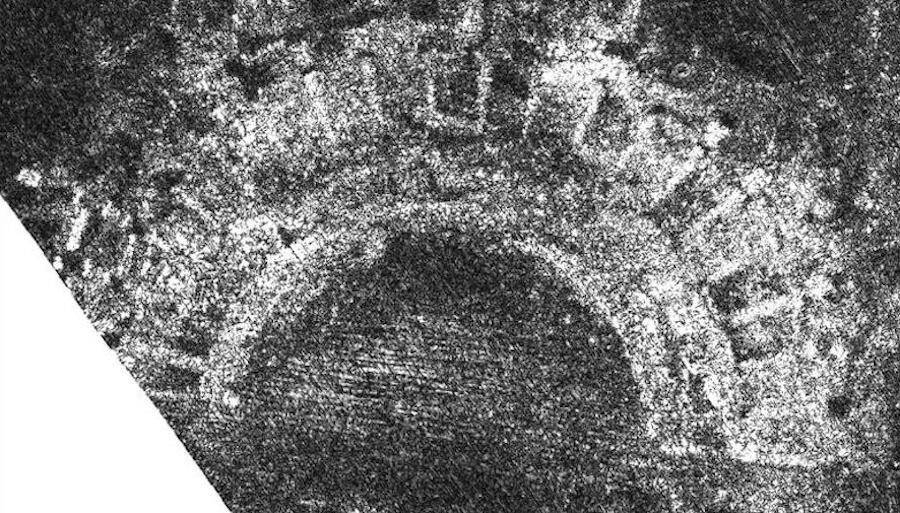

Verdonck et al., 2020/AntiquityThe ancient theater at Falerii Novi.

Though still mysteries in its function, Millett believes it likely stemmed from cultural and religious practices of the Faliscan people — those who occupied this region of Italy before it was conquered by Rome.