“How a Cataclysmic Eruption Shaped Napoleon’s Fate: The Surprising Link Between Indonesia and Waterloo”

On the night before Napoleon’s final battle, heavy rains flooded the Waterloo region of Belgium and as a result, the French Emperor elected to delay his troops. Napoleon was worried that the soggy ground would slow down his army.

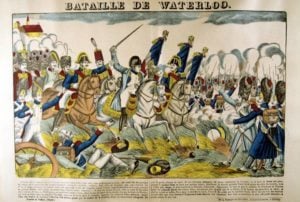

Wikimedia Commons

While that might have been viewed as a wise choice on Napoleon’s part, the extra time allowed the Prussian Army to join the British-led Allied army and help defeat the French. 25,000 of Napoleon’s men were killed and wounded, and once he returned to Paris, Napoleon abdicated his rule and lived the rest of his life in exile on the remote island of Saint Helena.

And none of that may have happened if not for one of the largest volcanic eruptions in history. The eruption of Mount Tambora could be heard from up to 1,600 miles away with ash falling as far as 800 miles away from the volcano itself. For two days after the explosion, the 350-mile region that surrounds the mountain was left in pitch darkness.

Dr. Matthew Genge, a professor at Imperial College London, believes that Mount Tambora let out a plume of electrified volcanic ash so enormous that it might have affected the weather in places as far off as Europe. The ash effectively “short-circuited” the electrical currents in the ionosphere: the upper section of the atmosphere where clouds form.

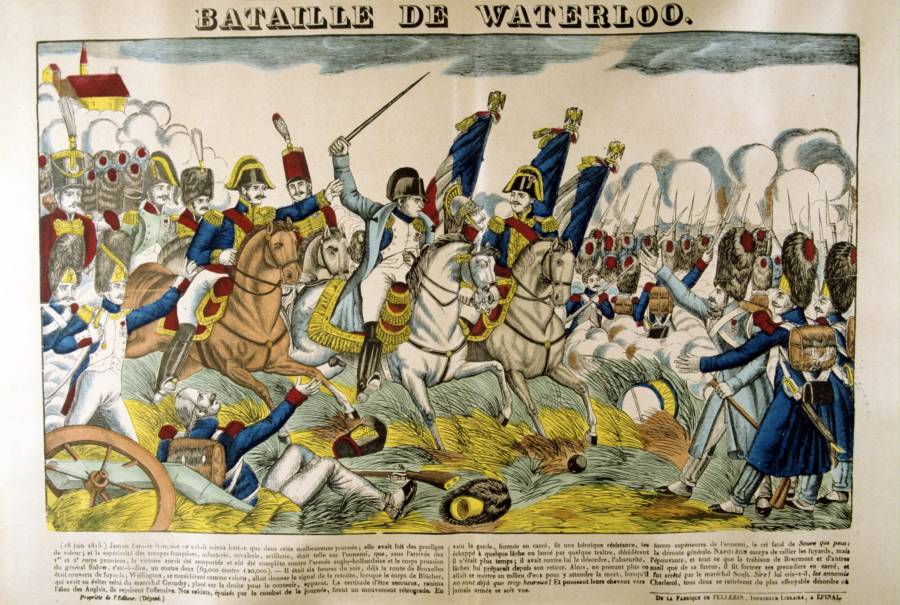

Universal History Archive/Getty ImagesNapoleon at the Battle of Waterloo in June 1815.

Geologists previously believed that volcanic ash could not reach this uppermost region of the atmosphere but Dr. Genge’s research proves otherwise. He posits that electrically charged volcanic ash can repel negative electrical forces in the atmosphere, leaving the ash to levitate in the atmosphere.