Scientists Unlock the Secret Formula of an Enigmatic Medieval Blue Ink Lost for Centuries

Who knew medieval scribes were rocking a blue pigment so unique, it’s like the unicorn of inks? Back when plants were the paint shops of choice, these natural blues vanished from the spotlight around the 17th century as flashy mineral dyes stole their thunder. But here’s the kicker—science just cracked open a centuries-old Portuguese recipe, resurrecting the long-lost blue known as folium, and it’s apparently “in a class of its own.” Imagine that, a pigment neither indigo nor your garden-variety flower dye, but something totally new and mesmerizing that’s been hiding in plain sight on ancient manuscripts. This discovery isn’t just a win for historians and conservators—it’s like finding the secret sauce to preserving the medieval world’s true colors for future generations to marvel at. Ready to see blue in an entirely new light?

The ink contains a newly discovered type of blue pigment that researchers say is “in a class of its own.”

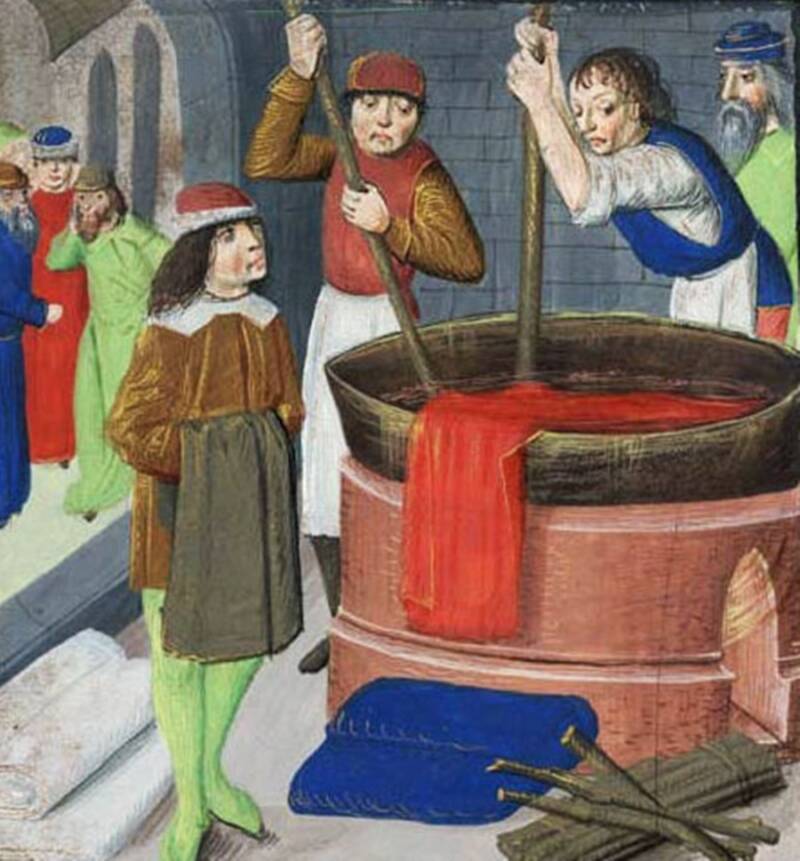

Wikimedia CommonsNatural coloring extracts from plants were commonly used to dye clothing in the Middle Ages.

During the Middle Ages, ink colors were naturally derived from plants. These naturally-colored inks fell out of style sometime around the 17th century when more vibrant mineral-based colors became available.

Sadly, the knowledge needed to make many of those natural inks was also lost until now. The recipe for medieval blue ink has just been resurrected by scientists following an old Portuguese recipe.

According to Science Alert, a team of researchers in Portugal successfully deciphered an ancient manuscript containing a recipe for the long-lost natural blue dye known as folium. They have just made the medieval blue dye for the first time in the 21st century.

The results of the study — which was published in Science Advances — will enable conservators to better preserve the medieval color and help historians easily identify it in old manuscripts.

“This is the only medieval color based on organic dyes that we didn’t have a structure for,” said Maria João Melo, a researcher of conservation and restoration at Lisbon’s NOVA University and a lead author of the new study.

Paula Nabais/NOVA UniveristyScientists were able to recreate the Medieval blue pigment using a coloring recipe from a 15th century manual.

“We need to know what’s in medieval manuscript illuminations because we want to preserve these beautiful colors for future generations.”

Melo and her team examined the recipe from a Medieval Portuguese treatise with the straightforward title The Book On How To Make All The Colour Paints For Illuminating Books. The book dates back to the 15th century but the text of the manuscript itself dates further, likely as far as the 13th century, and was written in Portuguese using Hebrew phonetics.

The book belonged to an “illuminator” who worked in the tradition of this remarkable coloring technique. Researchers believe that the book’s main purpose was possibly to “assist on the production of Hebrew Bibles, where the precision of the text would have been illuminated by the colors described in this ‘book of all color paints.’”

The medieval manual illustrates the necessary materials and has detailed instructions for creating the colors. It even notes the appropriate time to pick the pigment-containing fruits of the plant Chrozophora tinctoria, which was prized in medieval times but is now considered a weed.

“You need to squeeze the fruits, being careful not to break the seeds, and then to put them on linen,” co-author and chemist Paula Nabais told Chemical and Engineering News. That small detail is crucial since destroyed seeds release polysaccharides which form a gummy material that is impossible to purify, resulting in a poor-quality ink.

In 2018, the team began making the organic dyes from scratch using recipes from the manuscript. They first soaked the fruit in a methanol-water solution which they had to stir carefully for two hours. Then, the methanol was evaporated under a vacuum which left a crude blue extract that the team purified and concentrated, resulting in a blue pigment.

Wikimedia CommonsThe plant Chrozophora tinctoria also has medicinal properties that have been found through past studies.

Researchers also analyzed the chemical compound of the colors they recreated. Using advanced technology such as mass spectrometry and magnetic resonance, they found that the compound in the medieval blue dye was different than the blue pigment extracted from other plants.

The newly discovered chemical compound of C. tinctoria‘s natural blue pigment was named chrozophoridin.

“Chrozophoridin was used in ancient times to make a beautiful blue dye for painting, and it is neither an anthocyanin — found in many blue flowers and fruits — nor indigo, the most stable natural blue dye. It turns out to be in a class of its own,” the researchers wrote.

The blue pigment extracted from the C. tinctoria, however, did share a similar structure with a blue chromophore found in another plant — Mercurialis perennis or dog’s mercury which is normally used as a medicinal herb. The difference is that the blue chromophore of the C. tinctoria is actually soluble, enabling it to be turned into liquid dye.