“Uncovering the Hidden Genius: The Surprising Origins of the World’s First Machine Gun!”

Unperturbed at the initial rejection, Puckle continued to refine the design, patenting a better version of the gun a year later in 1718. Said patent, No. 418, describes the gun as being primarily for defensive purposes and notes that it is ideal for defending “bridges, breaches, lines and passes, ships, boats, houses and other places” from pesky foreigners.

A natural salesman, Puckle went as far as putting advertising of sorts right in his patent, with the second line of said patent reading: “Defending KING GEORGE your COUNTRY and LAWES – Is Defending YOUR SELVES and PROTESTANT CAUSE”

This is an idea Puckle would double down on by including engravings on the gun itself featuring things like King George, imagery of Britain and random bible verses.

To doubly sell potential investors on the value of the gun as a stalwart defender of Christian ideology, Puckle’s patent also describes how the gun could, in a pinch, fire square bullets.

What does this have to do with religion?

Puckle thought that square bullets would cause significantly more damage to the human body and believed that if they were shot at Muslim Turks (who the British were fighting at the time), it would, to quote the patent, “convince [them] of the benefits of Christian civilisation”.

The gun could also fire regular, round projectiles too (which Puckle earmarked as being for use against Christians only). On top of that, it also fired “grenados”, shot, essentially comprising of many tiny bullets- you know, for when you really wanted to ruin someone’s day.

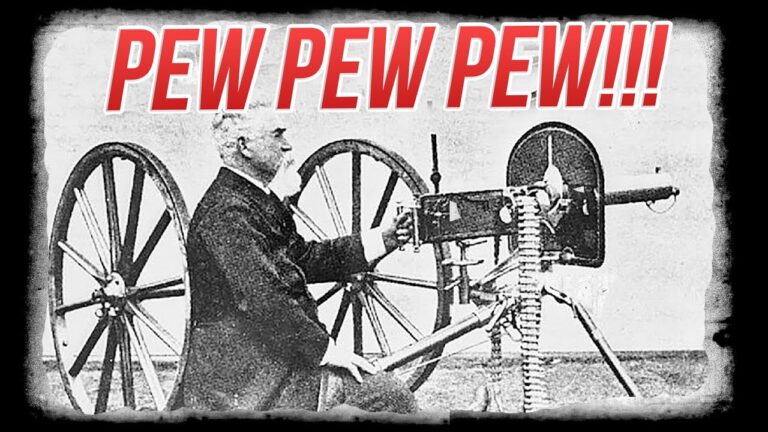

Puckle began selling shares of his company to the public in 1720 for about 8 pounds a piece (about £1,100 pounds or $1,600 today) to finance construction of more advanced Puckle Guns, one of which was demonstrated to the public on March 31, 1722.

During said demonstration, as described in the London Journal: “[O]ne man discharged it 63 times in seven Minutes, though all while Raining, and it throws off either one large or sixteen Musquet Balls at every discharge with great force…”

Despite the impressive and reliable display, the British military on the whole was still uninterested in the newfangled technology.

That said, there was at least one order, placed by then Master-General of Ordnance for Britain, Duke John Montagu, for two of the guns to bring along in an attempt to capture St. Vincent and St. Lucia in the Caribbean. Whether these ever ended up being used or not isn’t clear.

Summing up Puckles’ failed invention and company, one sarcastic reporter for the London Journal quipped that the gun had “only wounded [those] who have shares therein.” Burn.

In any event, it would be another century and a half before the first true rapid-fire weapon appeared on the battlefield: the French mitrailleuse. Invented in 1851 by Belgian Army Captain Toussaint Fafschamps, the mitrailleuse comprised a cluster of fifty rifled barrels mounted on a conventional wheeled artillery carriage. The ammunition, consisting of a lead bullet and paper cartridge fired by a spring-loaded needle, was held in a removable breech block which was inserted into the rear of the weapon. The operator then turned a crank on the side of the breech, which fired each barrel in quick succession. While Fafschamp’s design was adopted by the Belgian Army, it was soon improved by engineers Louis Christophe and Joseph Montigny, who in 1859 presented their 37-barrel version to French Emperor Napoleon III. Impressed, Napoleon ordered the immediate development of an improved version under the greatest of secrecy, paying for the whole project out of his personal funds. This resulted in the French Army officially adopting a 25-barrel mitrailleuse designed by Jean-Baptiste de Reffye in 1865

While today machine guns are mainly used like rapid-firing rifles for laying down suppressive fire or engaging quick-moving targets, the operational doctrine for the mitrailleuse was somewhat different. For much of history, artillery was equipped to fire not only single solid cannonballs or explosive shells, but also large numbers of smaller projectiles called grapeshot or canister shot for use against infantry at close range – effectively turning them into giant shotguns. In French, this type of ammunition is known as mitraille – hence the name mitrailleuse. However, in 1858 the French Army adopted a Beaulieu 4-pounder rifled field gun, which while considerably more accurate and long-ranged than earlier artillery, was not well-suited to firing anti-personnel rounds. Consequently, as Reffye pointed out:

“In combat are found many circumstances where infantry, finding itself within range of artillery, the latter cannot resist the rapid fire of the rifle and, if the infantry, not letting itself be intimidated by the detonations of the pieces and the bursting of the shells, marched resolutely towards batteries themselves undefended by infantry, it would soon reduce them to silence by eliminating their crews…Since the war of secession in America, one has sought to build a weapon which could imitate the rapidity of fire of the rifle, while surpassing it in range, reliably striking infantry and cavalry at distances where canister loses its effectiveness. The bullet-canon has thus been developed to go into action between 900 and 2500 metres, with more accuracy than the old grape-shot which seems almost to have fallen into disuse nowadays.”