“Uncovering the Hidden Genius: The Surprising Origins of the World’s First Machine Gun!”

Thus, the mitrailleuse was conceived not as a rapid-firing rifle, but as a longer-ranged version of canister shot, with the weapons being deployed alongside regular artillery batteries. The mitrailleuse first saw combat during the Franco-Prussian war of 1870-1871, but despite the Napoleon’s high hopes for his Army’s high-tech “secret weapon”, it proved a disappointment. However, this had more to do with French doctrine than the design of the weapon itself, for on those rare instances when it was used at close range, it proved devastatingly effective. As one observer noted at the September 1, 1870 Battle of Sedan:

“On the heights, close to Floeing, there was placed a battery of Mitrailleuses. There is, opposite to that, a round hill with wood on the top; and out of this wood and from behind this hill came the Prussian columns. As they came out they were swept down by these Mitrailleuses, and they did not succeed. They could not make any progress, but were obliged to go back again, and go round on the reverse slope of the hill, checked by the Mitrailleuse.”

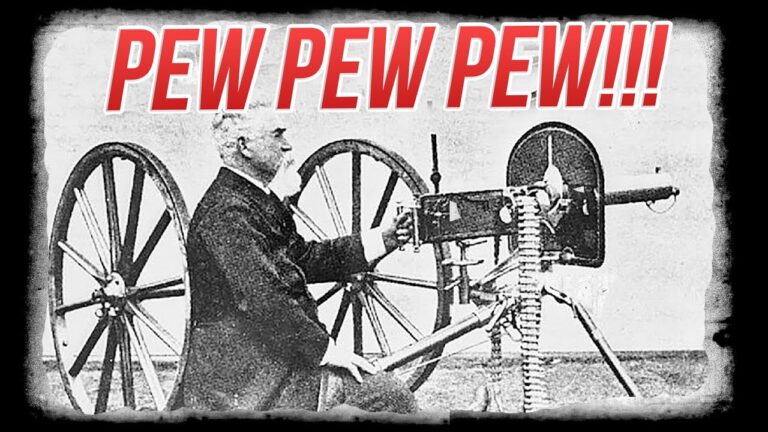

But despite the mitrailleuse being the first rapid-fire weapon to see combat in large numbers – indeed, in modern French the term mitrailleuse means “machine gun” – it is more properly classified as a volley gun than a proper machine gun since the ammunition is loaded manually rather than automatically. Much closer to the modern definition was the Gatling gun, patented by American inventor Dr. Richard J. Gatling in 1861. Unlike the mitrailleuse, whose barrels were fixed, the Gatling gun’s ten barrels rotated around a central shaft, driven by a hand crank. As a barrel rotated into the top position, a cartridge dropped from a gravity-fed hopper and was automatically loaded into the chamber. When the barrel reached the bottom position, the cartridge was fired. The empty cartridge was then ejected from the chamber before the barrel reached the top position and the whole cycle began anew. The use of multiple barrels allowed each one to cool off between firings, preventing the weapon from overheating and allowing it to sustain continuous fire at a rate of up to 200 rounds per minute.

Gatling’s inspiration for creating his gun was surprisingly humanitarian. As a physician, Gatling knew that the vast majority of casualties in war were not caused by bullets or shells but disease. Thus, as he later wrote to a friend in 1877:

“It occurred to me that if I could invent a machine – a gun – which could by rapidity of fire, enable one man to do as much battle duty as a hundred, that it would, to a great extent, supersede the necessity of large armies, and consequently, exposure to battle and disease be greatly diminished.”

But like all weapons intended to be so powerful they would end war, the Gatling gun only succeeded in increasing its efficiency and bloodiness. While the Union Army refused to adopt the weapon during the Civil War on the grounds of complexity and cost, Gatling guns did see use at the siege of Petersburg, Virginia, in the spring of 1865. Based on its brutal effectiveness in that battle, the Army finally adopted the Gatling gun the following year. Other nations soon followed, including the British Empire, Argentina, Peru, Siam, and Korea. But while the Gatling gun was originally intended for use by and against modern, industrialized armies, it was most effectively employed against poorly armed opponents in colonial wars. For example, the British Empire used Gatling guns to devastating effect against the Zulu in South Africa and the Mahdists in Sudan, while back in the United States the weapon was widely deployed against Native Americans and striking workers.

Several other hand-cranked machine guns were developed during this period including the single-barrelled Agar or “coffee mill” gun, introduced in 1861 and used in limited numbers during the Civil War – mainly to guard bridges, narrow passes, and other strategic targets. There was also the Gardner Gun and the multiple-barrelled Nordenfelt gun, both used in small numbers by the British Army and Royal Navy. But while such manually-operated firearms were eventually superseded by more advanced self-loading types, the Gatling gun mechanism lives on in modern aircraft-mounted rotary-barrelled cannons like the M61 Vulcan and the GAU-8 Avenger, which are driven by electric motors. And in 1963, General Electric miniaturized the mechanism to chamber the 7.62x51mm NATO cartridge, creating the famous M134 Minigun immortalized in such films as Predator and Terminator 2. Thanks to their electric drives and the self-cooling properties of the multi-barrel design and the high speed, these weapons are able to reach blistering rates of fire up to 6,000 rounds per minute.

But while closer to the modern definition of a machine gun, the Gatling, Agar, Gardner, Nordenfelt and their ilk still lacked one critical feature: self-loading – the ability to use the leftover energy from a fired cartridge to cycle the action automatically. While many inventors throughout the 19th Century attempted to develop such a weapon, they were all stymied by the same technical limitation: gunpowder. Virtually unchanged since its invention in China in the 9th Century, black gunpowder created large amounts of residue or fouling that quickly clogged up the mechanisms of early would-be machine guns, making sustained fire impossible. In 1886, however, the French Army introduced an innovation that would change the face of warfare: Poudre B or “smokeless powder”, which burned hotter, faster, and cleaner than traditional gunpowder. And as luck would have it, just two years earlier an American inventor had patented the perfect weapon to use this new powder.