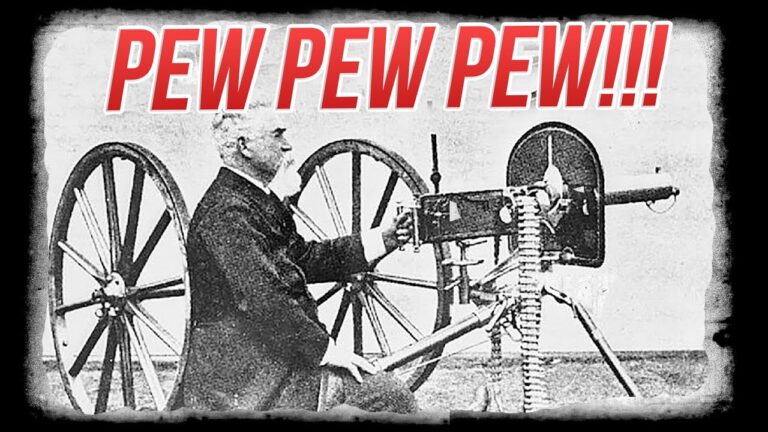

“Uncovering the Hidden Genius: The Surprising Origins of the World’s First Machine Gun!”

Born in 1840 in Sangerville, Maine, Sir Hiram Stevens Maxim was a prolific inventor, his various creations including a bronchitis inhaler, the first automatic fire sprinkler system, an early version of the lightbulb, and an amusement park ride called the “Captive Flying Machine” which is still used to this day. He was also one of many inventors competing with the Wright Brothers to build the first powered, heavier-than-air flying machine. But Maxim’s greatest claim to fame would come as a result of a chance encounter in 1882. As he later recounted to the Times of London:

“I was in Vienna, where I met an American whom I had known in the States. He said: ‘Hang your chemistry and electricity! If you want to make a pile of money, invent something that will enable these Europeans to cut each other’s throats with greater facility.’ ”

Over the next four years, Maxim toiled in his London workshop to perfect such a weapon, which he inevitably dubbed the Maxim Gun. Unlike its predecessors, the Maxim Gun was recoil-operated, using the recoil impulse generated by each cartridge firing to push back the sliding barrel and cycle the weapon’s action – no hand-cranking or other external power source required. The weapon was fed from a long cloth belt of ammunition while its barrel was wrapped in a metal jacket full of cooling water, allowing it to sustain firing rates as high as 600 rounds per minute for long periods of time. When first introduced, the Maxim gun was designed to use then-standard black powder cartridges; however, it was soon adapted for the newly-invented smokeless powder.

In 1886, with funding from the Vickers engineering firm, Maxim founded the Maxim Gun Company to produce and sell his invention. Though it was more reliable and could deliver greater firepower than any other weapon on the market, the real genius of Maxim’s design lay in its adaptability; by swapping out just a handful of parts, the weapon could be made to shoot just about any cartridge. This made the gun an immediate international bestseller, with over 30 countries ordering Maxim guns in dozens of different calibers. Like the Gatling gun before it, the Maxim soon became closely associated with colonial conquest – especially during the late 19th Century “Scramble for Africa.” For example, during the 1893-1894 Matabele War in what is now Zimbabwe, British Maxim guns succeeded in holding off a force of 5,000 Ndebele warriors – killing some 1,600. Indeed, the battle was so lopsided that some surviving warriors committed suicide by throwing themselves onto their spears.

Like Richard Gatling 20 years before, many believed that the Maxim Gun would make war between civilized nations unthinkable, bringing about a new era of peace. As the New York Times argued in 1897:

“These are the instruments that have revolutionized the methods of warfare, and because of their devastating effects have made nations and riles give greater thought to the outcome of war before entering…They are peace-producing and peace-retaining terrors.”

But they were to be proven tragically wrong just 17 years later with the outbreak of the First World War – a conflict synonymous with the Maxim gun and industrialized slaughter. Though far more troops were killed by artillery than machine guns, the latter had an outsized psychological impact, cutting down scores of men like corn beneath the scythe and turning no-man’s-land between the trenches into impassable death traps. But the bloody stalemate the Maxim gun helped preserve also drove innovation in machine gun design. While reliable and deadly, the regular Maxim gun was heavy, awkward to move around, and required a team of at least four men to operate efficiently. Regaining the type of mobile warfare which had dominated the early months of the war required lighter, handier weapons that could be carried and operated by fewer men and deployed on the move. This requirement led to the development of a new generation of light machine guns like the British Lewis Gun, the French Chauchat, and the American Browning Automatic Rifle, which – along with improved tactics involving the coordinated use of artillery, aircraft, and tanks – eventually helped break the stalemate and bring about the Armistice of 1918. The machine gun’s place in modern warfare was secured.

While the Maxim Gun has largely been superseded by more modern designs, the OG machine gun continues to see service to this very day, with many examples recently showing up in the conflict in Ukraine. But what did Sir Hiram Maxim think of his most famous creation’s deadly legacy? While outwardly pleased by his success, Maxim at least seemed aware of the disturbing hypocrisy of the world around him. Shortly before the outbreak of the First World War, Maxim – a lifelong bronchitis sufferer – invented a new type of medical inhaler which dispensed soothing pine vapour. The invention drew scorn from his fellow inventors, who accused him of “prostituting his talents” on quack science. To this accusation, Maxim responded: