Uncovering the Secrets of a 30,000-Year-Old Ice Age Hunter’s Toolkit in the Czech Republic

Imagine stumbling upon a nearly 30,000-year-old toolbox—except instead of wrenches and screwdrivers, you’ve got 29 meticulously arranged stone blades and points once snug inside a long-decayed leather pouch. How do you even lose something like that during the Ice Age? Archaeologists in the Czech Republic pose just that intriguing question after unearthing this remarkably intact Paleolithic toolkit, frozen in time at a transient hunting camp. This isn’t just a pile of old rocks; it’s a rare, almost intimate snapshot of one hunter’s day-to-day life, revealing not only how tools were crafted and maintained but hinting at vast trade networks stretching across Ice Age Europe. So next time you misplace your keys, remember: ancient hunters faced their own version of the “Where’s my stuff?” conundrum, albeit with a touch more survival on the line. LEARN MORE

The intact set of 29 blades and points was likely once carried in a leather pouch that disintegrated long ago.

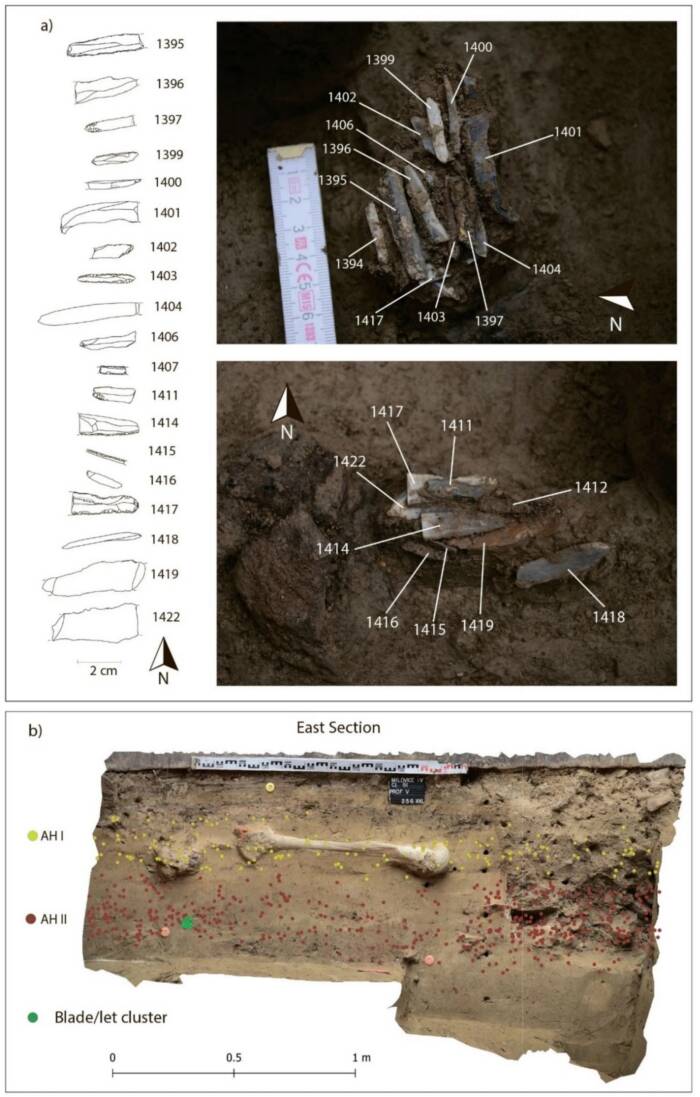

Martin NovákThe bundle of Ice Age tools unearthed at the Milovice IV archaeological site in the Czech Republic.

Archaeologists in the Czech Republic have uncovered a remarkably well-preserved toolkit dating back roughly 30,000 years. Now, it’s shedding light on how Paleolithic hunters organized and maintained their gear while traveling across Ice Age Europe.

The collection, discovered in southern Moravia, consists of 29 blades and points that were found gathered together in a single cluster. Researchers believe the tools were once bundled in a pouch that decayed long ago, leaving behind the exact configuration of a hunter’s tools.

“This assemblage appears to represent a personal toolkit that was either lost or discarded,” wrote Dominik Chlachula and colleagues in a study published in the Journal of Paleolithic Archaeology. “Insight into the lives of individuals is extremely rare for the Palaeolithic.”

A Rare Look Into The Daily Lives Of Paleolithic Hunters

The discovery was made during excavations at the Milovice IV archaeological site. The artifacts were recovered from a layer containing charcoal that dated back to between 30,250 and 29,550 years ago. The layer also included animal bones — mainly from horses and reindeer — and a fireplace, indicating that the toolkit was part of a temporary hunting camp.

Unlike many Paleolithic artifacts that are found in disturbed or mixed deposits, this toolkit remained largely untouched, providing a rare and rather intimate glimpse into the life of an Ice Age hunter-gatherer.

The toolkit was likely carried during a hunt and then either lost or intentionally left behind. “The cluster can be interpreted as personal gear used during hunting expeditions, regularly maintained and occasionally modified until its eventual discard or loss in a residential camp,” the researchers wrote.

Journal of Paleolithic ArchaeologyThe cluster of tools in situ.

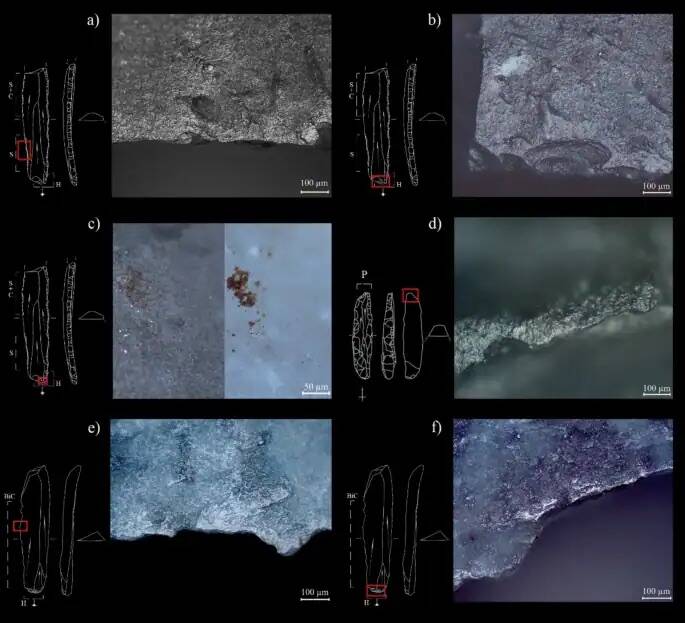

Analysis revealed that the 29 artifacts were not a random assortment. The larger blades were used for processing medium to hard materials, while the smaller blades show wear consistent with cutting soft materials or working with animal hide. Six artifacts displayed fractures typically associated with projectiles, and at least one carried microscopic linear impact traces (MLITs), confirming that it had been used as a point on an arrow or spear.

Perhaps more fascinating, however, is where these tools originated.

Evidence Of Long-Distance Trade Networks

The raw materials used to make the blades and points from the toolkit came from far beyond the site where they were found. Of the 29 artifacts, 19 were made of erratic flint from glacial deposits more than 80 miles to the north. Seven were made of radiolarite, likely from western Slovakia, and one was fashioned from opal sourced between 70 and 85 miles away.

“The variability of raw materials within the cluster can be attributed to several factors: direct collection by the bearer or their group from outcrops or other natural sources; exchange or sharing among groups or individuals visiting different raw material sites; reuse of older blanks from abandoned camps or workshops; collection from caches; or a combination of these practices,” the authors wrote.

Journal of Paleolithic ArchaeologyTraces of wear were seen on the blades.

This distribution suggests the hunter either traveled long distances or participated in an extensive exchange network, though there is no evidence that can definitively confirm or dismiss any of these theories. The absence of larger tools like scrapers, however, suggests the toolkit was designed for lightweight mobility. More complex processing tasks likely took place back at base camps.

What makes the Milovice IV find extraordinary is its clear connection to a single person’s daily life. Most Paleolithic finds are either isolated tools or large, mixed deposits representing entire camps.

This cluster, by contrast, captures a moment in time: a single hunter’s set of tools, prepared for a journey across the frozen landscape of Ice Age Europe, offering rare insight into daily life during the Gravettian period.