“Unlock the Secrets of 8 Centuries-Old Etiquette Rules That Could Transform Your Political Conversations Forever!”

As the holidays approach, do you ever wonder what it would take to keep Uncle Joe from turning Thanksgiving dinner into a political debate that rivals a heavyweight boxing match? With families gathering around the table, it’s almost like a recipe for disaster—different opinions simmering beneath the surface, just waiting to boil over. Thankfully, we’ve got an unusual lifeline from the 19th century. Believe it or not, etiquette experts from back then had some surprisingly relevant advice to help us navigate the treacherous waters of political chatter. Whether you’re a seasoned debater or the quiet peacemaker of the family, these timeless tips will empower you to engage in civilized discussions, even with that one relative who thinks he’s a political guru. So, let’s step back, take a deep breath, and remember: politics doesn’t have to be ugly! Curious about how to keep your holiday discussions harmonious? **[LEARN MORE](https://www.mentalfloss.com/section/holidays)**.

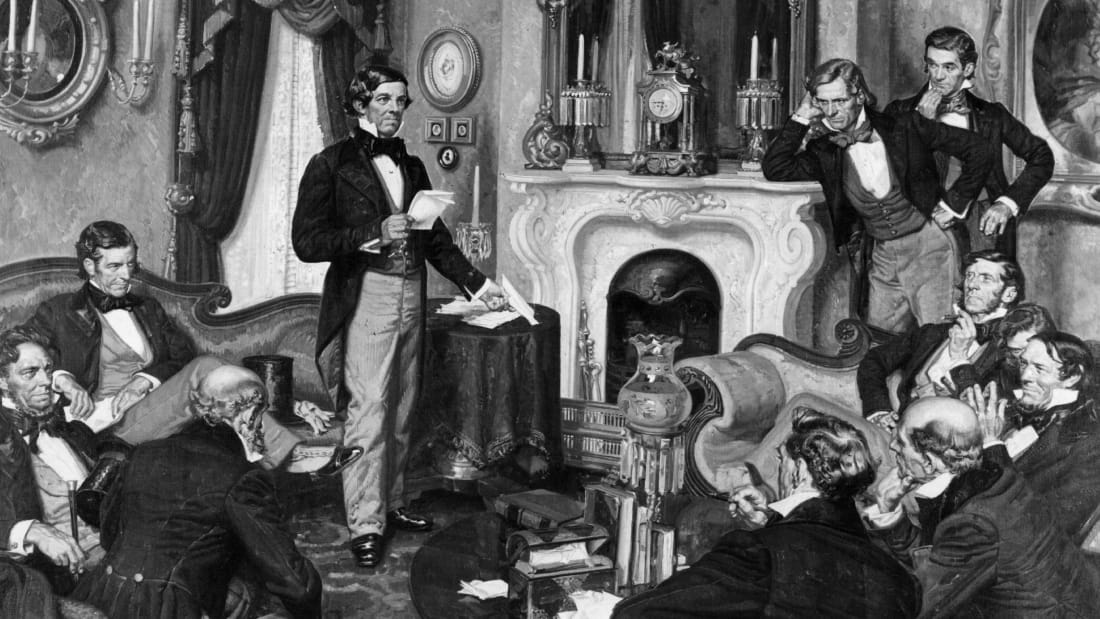

It can sometimes be easy to forget that a civilized political discourse is possible—especially around the holidays, when family members with vastly different viewpoints gather around one table. Doing your best to rise above the fray? Nineteenth century etiquette experts were full of (surprisingly) timeless pieces of advice for discussing issues with friends, colleagues, and family members. Keep this list handy this holiday season, and remember: Politics can get ugly, but the drawing room conversation doesn’t have to.

Educate yourself before you open your mouth.

“It is very needful for one who desires to talk well, not only to be well acquainted with the current news, and modern and ancient literature of his language, but also with the historical events of the past and present of all countries. He must not have a confused idea of dates and history, but be able to give a clear account, not only of the chief events of the recent Rebellion, but also of those of the Revolutions of the past century, and of the period of the Roman Empire, its rise and fall, and of the various important events which have occurred in England, France, Italy, Germany, Switzerland, Turkey, and Russia.”

— From Daisy Eyebright’s A Manual of Etiquette With Hints on Politeness and Good Breeding, 1873

Know where you stand …

“Retain, if you will, a fixed political opinion, yet do not parade it upon all occasions, and, above all, do not endeavor to force others to agree with you. Listen calmly to their ideas upon the same subjects, and if you cannot agree, differ politely, and while your opponent may set you down as a bad politician, let him be obliged to admit that you are a gentleman.”

— From Cecil B. Hartley’s A Gentleman’s Guide to Etiquette, 1875

… But don’t be a know-it-all.

“Never, when advancing an opinion, assert positively that a thing ‘is so,’ but give your opinion as an opinion. Say, ‘I think this is so,’ or, ‘these are my views,’ but remember that your companion may be better informed upon the subject under discussion, or, where it is a mere matter of taste or feeling, do not expect that all the world will feel exactly as you do.”

— From Florence Hartley’s The Ladies’ Book of Etiquette and Manual of Politeness, 1860

Don’t monopolize the conversation.

“A man is sure to show his good or bad breeding the instant he opens his mouth to talk in company … The ground is common to all, and no one has a right to monopolize any part of it for his own particular opinions, in politics or religion. No one is there to make proselytes, but every one has been invited, to be agreeable and to please.”

— From Arthur Martine’s Martine’s Hand-Book of Etiquette and Guide to True Politeness, 1866

Know when to change the subject.

“Whenever the lady or gentleman with whom you are discussing a point, whether of love, war, science or politics, begins to sophisticate, drop the subject instantly. Your adversary either wants the ability to maintain his opinion … or he wants the still more useful ability to yield the point with unaffected grace and good humor; or what is also possible, his vanity is in some way engaged in defending views on which he may probably have acted, so that to demolish his opinions is perhaps to reprove his conduct, and no well-bred man goes into society for the purpose of sermonizing.”

— From Martine’s Hand-Book of Etiquette and Guide to True Politeness

Keep your cool, too.

“Even if convinced that your opponent is utterly wrong, yield gracefully, decline further discussion, or dexterously turn the conversation, but do not obstinately defend your own opinion until you become angry … Many there are who, giving their opinion, not as an opinion but as a law, will defend their position by such phrases, as: ‘Well, if I were president or governor, I would,’—and while by the warmth of their argument they prove that they are utterly unable to govern their own temper, they will endeavor to persuade you that they are perfectly competent to take charge of the government of the nation.”

— From A Gentleman’s Guide to Etiquette

Whatever you do, do not take sides.

“In a dispute, if you cannot reconcile the parties, withdraw from them. You will surely make one enemy, perhaps two, by taking either side, in an argument when the speakers have lost their temper.”

— From A Gentleman’s Guide to Etiquette

Try not to criticize politicians … if there are politicians present.

“It is bad manners to satirize lawyers in the presence of lawyers, or doctors in the presence of one of that calling, and so of all the professions. Nor should you rail against bribery and corruption in the presence of politicians … or members of Congress, as they will have good reason to suppose that you are hinting at them.”

— From Martine’s Hand-Book of Etiquette and Guide to True Politeness

Read More About Politics:

feed

A version of this story ran in 2016; it has been updated for 2024.