“Unraveling the Mystery: The Shocking Truth Behind ‘Dum-Dum’ Bullets Revealed!”

What’s in a name? If you’ve ever chuckled at the cleverness of cartoonish humor, you might have found yourself pondering just how a “Dum-Dum” bullet found its way into our language, especially when it pops up in unexpected places like the hilarious antics of Eddie Valiant in *Who Framed Roger Rabbit?* Picture it: a fed-up detective, armed with cartoonish firepower that misfires like a scene out of a slapstick comedy, muttering “Dum Dums…” under his breath—it’s funny, sure, but it also makes you wonder what’s behind that phrase.

Why would such a silly-sounding term be attached to one of the most destructive forms of ammunition in history? I mean, imagine a world where “Dum-Dum” bullets are not just the punchline of a joke, but lead to serious discussions about warfare and ethics. It begs the question: what makes these things so notably “dumb,” and why have they been banned in combat for over a century?

So, let’s dive into this intricate tale of ammunition that’s steeped in irony, tragedy, and a bit of dark humor!

Near the end of the groundbreaking 1988 hybrid live-action/animation film Who Framed Roger Rabbit? hardboiled detective Eddie Valiant is in hot pursuit of three villainous cartoon weasels, who escape through a tunnel into the animated ghetto of Toon Town. Before following them in, Valiant pulls out and loads a cartoon gun given him by none other than Yosemite Sam, whose bullets look and talk like characters from classic westerns – because, sure, why not? Later, he fires this revolver at the weasels, only for the bullets to suddenly halt mid-flight, look around in confusion, and fly off in the completely wrong direction – prompting Valiant to sigh and dejectedly mutter “Dum Dums…” While this comment likely flew over the heads of every child watching the film, it is, of course, a clever pun on an infamously destructive type of ammunition: the so-called Dum-Dum bullet. But what is a Dum-Dum anyway? What makes it so destructive? Why has its use in warfare been banned for over 120 years? And where did it get its strange name? Well let’s dive into it, shall we?

Near the end of the groundbreaking 1988 hybrid live-action/animation film Who Framed Roger Rabbit? hardboiled detective Eddie Valiant is in hot pursuit of three villainous cartoon weasels, who escape through a tunnel into the animated ghetto of Toon Town. Before following them in, Valiant pulls out and loads a cartoon gun given him by none other than Yosemite Sam, whose bullets look and talk like characters from classic westerns – because, sure, why not? Later, he fires this revolver at the weasels, only for the bullets to suddenly halt mid-flight, look around in confusion, and fly off in the completely wrong direction – prompting Valiant to sigh and dejectedly mutter “Dum Dums…” While this comment likely flew over the heads of every child watching the film, it is, of course, a clever pun on an infamously destructive type of ammunition: the so-called Dum-Dum bullet. But what is a Dum-Dum anyway? What makes it so destructive? Why has its use in warfare been banned for over 120 years? And where did it get its strange name? Well let’s dive into it, shall we?

From the introduction of practical shoulder arms in the 15th Century, ammunition largely took the form of spheres or musket balls cast from solid lead. Lead had many advantages as an ammunition material. It melted at a low temperature and was easy to cast; was dense and delivered significant terminal energy on impact and; when rifled firearms began to appear, was soft enough for the spin-stabilizing grooves or rifling in the barrel to bite into. Soft lead bullets also tended to deform on impact, expanding beyond their original diameter and carving out larger, more destructive – and more lethal – wounds.

Musket balls remained the standard form of small-arms ammunition for nearly 400 years until, in the 1840s, inventors like Captain John Norton, William Greener, Colonel Claude Étienne Minié, and Colonel James Burton developed what came to be known as the Minié Ball, a streamlined conical bullet with a conical or hemispherical hollow in the base. This design neatly solved a key problem which had previously prevented the wide-scale adoption of rifled firearms. Up until this point, nearly all military firearms were muzzle-loaders, meaning a soldier first had to pour a measured quantity of gunpowder down the barrel, then insert a musket ball and push it down against the powder charge using a ramrod. As musket balls tended to be slightly smaller than the barrel diameter or bore, this process was fairly rapid and a well-trained soldier could fire up to three aimed shots per minute. Rifled firearms, however, require the bullet to be the same diameter as the bore so that the rifling can cut into it. This makes the bullet much harder to ram down the barrel, significantly slowing down the firing rate. And this problem only became worse as powder residue built up inside the barrel, progressively fouling up the rifling. For this reason, until the mid-19th Century rifles were mainly issued to sharpshooters and other specialists, while the rank-and-file used regular smoothbore muskets. The Minié ball, by contrast, was slightly smaller than the bore, allowing it to be easily rammed down. When the rifle was fired, however, the pressure of the propellant gases behind the bullet caused the thin lead “skirt” formed by the hollow base to expand, sealing or obturating the bullet against the barrel and causing it to “bite” into the rifling. This design extended the range of shoulder arms from 50 to nearly 300 yards while maintaining their firing rate, revolutionizing warfare almost overnight. Indeed, during the Crimean War of 1853-56, it was estimated that 150 men firing Minié balls from rifled muskets had the equivalent firepower of 500 men using older smoothbore muskets.

But the Minié ball changed warfare in another, gruesome way. While earlier musket balls tended to be stopped by bone and become lodged in soldiers’ bodies, the lighter, faster Minié balls usually passed straight through. This, combined with the soft lead bullets’ tendency to deform and expand, often resulted in shattered bones and large, gaping wound channels. Such injuries very quickly became infected, prompting field surgeons to immediately amputate wounded arms and legs. Indeed, during the American Civil War of 1861-65, Minié ball wounds accounted for nearly 75% of all amputations – of which some 50,000 were performed by both sides throughout the conflict.

But even more destructive weapons were beginning to appear on the battlefield. In 1857, British Army Major John Jacob developed bullets filled with explosive potassium chlorate that would detonate on impact, designed for blowing up enemy ammunition magazines at ranges of up to 1,000 yards. In the early 1860s, New York firearms dealer Samuel Gardiner Jr. adapted Jacobs’s design to fit inside a standard U.S. Army .58 calibre Minié ball. Unlike the earlier Jacobs bullet, which had to strike a solid surface to explode, Gardiner’s design was set off by a delay fuse ignited by the rifle’s propellant charge, and could be set to explode at any point along its trajectory. It was also cast from harder zinc or pewter instead of lead to increase its fragmentation effect. In early 1862 Gardiner presented his invention to the Union government for evaluation, whereupon President Abraham Lincoln, eager to acquire the very latest in military technology for his army, pushed for its adoption. By December of that year, an order for 100,000 Gardiner musket shells was placed for use in field trials.

Almost immediately, the new bullets attracted controversy and condemnation. Though intended, like the Jacob bullet, for use against enemy ammunition stores and other such targets, the Gardiner shells were inevitably used as anti-personnel weapons – with predictably gruesome results. Indeed, the Union Army’s Chief of Ordnance, General James W. Ripley, had been dead-set against the Gardiner shell from the beginning and repeatedly tried to block its adoption before finally being overruled my Lincoln. Many others were equally hostile, with General Ulysses S. Grant condemning the Gardiner shell as:

“…barbarous, because they produce increased suffering without any corresponding advantage to those using them.”

…and General A.B. Dyer, Ripley’s successor as Chief of Ordnance, declaring the weapons:

“…inexcusable among any people above the grade of ignorant savages.”

Meanwhile, similar objections were being raised in Russia, where in 1863 an impact-sensitive explosive bullet similar to Jacobs’s design was introduced for blowing up powder magazines and ammunition wagons. By 1867, a more sensitive version was developed which would detonate on impact with even soft targets like humans or animals. But while most nations might have exploited this technological edge to their strategic advantage, the Russians, fearing that this gruesome new weapon would trigger a deadly European arms race, instead sought to ban further development of explosive ammunition. In December 1868, delegates from 18 European nations – Austria-Hungary, Bavaria, Belgium, Denmark, France, the United Kingdom, Greece, Italy, the Netherlands, Persia, Portugal, Prussia, Russia, Sweden-Norway, Switzerland, the Ottoman Empire, and Württemberg – gathered in St. Petersburg to further amend the international laws of war. This was only the second time such an effort had been undertaken after the First Geneva Convention of 1864, which laid out the rules for treatment of the wounded on the battlefield. The resulting treaty, dubbed the Declaration Renouncing the Use, in Time of War, of Explosive Projectiles Under 400 Grammes Weight or simply the The Saint Petersburg Declaration of 1868, was signed by all 18 attending delegates, and read, in part:

“On the proposition of the Imperial Cabinet of Russia, an International Military Commission having assembled at St. Petersburg in order to examine the expediency of forbidding the use of certain projectiles in time of war between civilized nations, and that Commission having by common agreement fixed the technical limits at which the necessities of war ought to yield to the requirements of humanity, the Undersigned are authorized by the orders of their Governments to declare as follows:

That the progress of civilization should have the effect of alleviating as much as possible the calamities of war;

That the only legitimate object which States should endeavour to accomplish during war is to weaken the military forces of the enemy;

That for this purpose it is sufficient to disable the greatest possible number of men;

That this object would be exceeded by the employment of arms which uselessly aggravate the sufferings of disabled men, or render their death inevitable;

That the employment of such arms would, therefore, be contrary to the laws of humanity;

The Contracting Parties engage mutually to renounce, in case of war among themselves, the employment by their military or naval troops of any projectile of a weight below 400 grammes, which is either explosive or charged with fulminating or inflammable substances.”

In other words, the delegates agreed that for projectiles weighing less than 400 grams, kinetic energy alone is enough to accomplish the task of killing or wounding a single person. Thus, adding additional explosives to such projectiles has no useful military effect and serves only to unnecessarily increase suffering. Also, in addition to conventional explosive projectiles which detonate on impact, the Declaration banned the military use of so-called “fulminating” projectiles, which contain a small charge of unstable explosive and are designed to shatter into fragments inside the wound or while being removed during surgery. On the other hand, larger explosive artillery or autocannon shells intended for use against fortified targets or to wound or kill multiple people were exempted from the declaration.

The United States, not considered a major military power at the time, was not invited to the St. Petersburg Convention and was not legally bound by its prohibitions. However, many senior American military officers like Chief of Ordnance Dyer agreed with its conclusions, and vehemently opposed the further adoption of exploding or fulminating small arms ammunition. Meanwhile, horrified by the nasty wounds inflicted by even standard-issue Minié balls, in the 1870s former Civil War surgeons and other medical professionals pushed for a national ban on soft lead bullets in warfare.

Though they were ultimately unsuccessful, the days of the Minié ball were nonetheless numbered – not due to any moral outrage, but rather the inexorable onward march of firearms technology. By the 1870s muzzle-loading rifled muskets had given way to single-shot breech-loading rifles firing self-contained cartridges – which combined the bullet, powder charge, and percussion cap into one convenient package – while by the 1880s repeating, magazine-fed rifles were starting to be widely adopted by the world’s armies. While the first self-contained cartridges used plain cast-lead bullets, these were soon found to be troublesome to use in repeating rifles, as the action of extracting a cartridge from the magazine and inserting it into the chamber tended to deform the bullet, leading to feeding problems, jams, and other issues. Thus, in 1882 Swiss Colonel Eduard Rubin, working for the Swiss Federal Ammunition Factory and Research Centre, developed the jacketed bullet, consisting of a lead core coated in a thin layer of copper, or brass. This jacket was hard enough to prevent the bullet from deforming but soft enough to engage with the barrel’s rifling, allowing for much smoother operation of the rifle.

Furthermore, the year 1886 saw a paradigm shift in firearms design with the introduction of the French Fusil Modele 1886 Lebel, the first standard military rifle to use the revolutionary new technology of smokeless powder. Unlike traditional black powder, smokeless powder did not produce the thick clouds of white smoke that previously obscured the battlefield, and left behind far less thick, corrosive residue in the rifle barrel. It also burned hotter and produced much higher chamber pressures than black powder, allowing bullets to travel faster and achieve flatter trajectories over longer ranges. As a result, bullets also became smaller. Previously, the particular chemistry of black powder had placed an upper limit on projectile velocity; thus, in order to maximize kinetic energy and terminal effect, bullets were made as heavy as possible. Kinetic energy, however, scales with the square of velocity, so once smokeless powder appeared on the scene it became more efficient to use smaller, lighter bullets travelling at much higher velocities. Thus, while black powder cartridges of the 1870s tended to use heavy, solid lead bullets 13-15 millimetres in diameter, smokeless powder cartridges of the 1880s and beyond had bullets half as wide. However, this increased performance came at a cost: plain lead bullets tended to shed their outer layers while travelling down the barrel, quickly fouling the rifling. Full metal jacket or FMJ bullets neatly solved this problem, and soon became standard for militaries around the world.

But no sooner had they entered service, the new high-velocity jacketed bullets were discovered to have an unexpected flaw. While fighting indigenous forces on the frontiers of the Empire, British colonial troops discovered that their bullets often passed straight through an attacking warrior without actually dropping them. As Major General Sir Charles John Ardagh, a veteran of the 1881-1899 Mahdist War in Sudan, explained in very dated language:

“The civilized soldier when shot recognizes that he is wounded and knows that the sooner he is attended to the sooner he will recover. He lies down on his stretcher and is taken off the field to his ambulance, where he is dressed or bandaged. Your fanatical barbarian, similarly wounded, continues to rush on, spear or sword in hand; and before you have the time to represent to him that his conduct is in flagrant violation of the understanding relative to the proper course for the wounded man to follow—he may have cut off your head.”

This problem was also encountered by other colonial powers. For example, during the Philippine-American War of 1899-1902, American troops discovered that neither their .30 calibre Krag-Jorgensen rifles or .38 calibre Colt 1892 revolvers had sufficient stopping power to halt a charging Moro tribesman. In April 1895, one Surgeon-Captain H. Hathaway of the British Indian Army observed an execution by firing squad conducted using the new .303 calibre Lee-Metford rifle. He noted that, in stark contrast to wounds inflicted by earlier soft-lead bullets, the holes produced by the .303 jacketed bullets were clearly defined, punching cleanly through bone instead of shattering it and causing very little damage to the surrounding tissue. In his report on the incident he concluded:

“Although [the Lee-Metford] is a very humane weapon, it is questionable whether it would stop a savage fanatical advance.”

Such reports caused the British colonial authorities a great deal of concern, and methods were immediately sought to improve the stopping power of weapons used in colonial conflicts. At first, soldiers field-modified their ammunition by cutting a cross in the tip of the bullet to promote expansion. Then, in 1896, Lieutenant Colonel Neville Sneyd Bertie Clay, superintendent of the Dum Dum Arsenal outside Calcutta, came up with a process for cutting away the front of the jacket on the standard Mk.II rifle bullet, exposing the lead core. Tests conducted on the cadavers of cows confirmed the effectiveness of the ammunition, and small numbers of so-called “Dum Dum” rounds were subsequently modified for issue to troops, first being used during the 1897-1898 Chitral and Tirah military expeditions on India’s Northwest Frontier. Based on this experience, in 1868 a Mark III “Dum Dum” cartridge was introduced with the front of the jacket cut away in the factory. However, due to production issues, the Mark III was almost immediately pulled from service and replaced by the Mark IV, which had a hollow cylindrical cavity extending back from the nose of the bullet. At the same time, a Mark III “manstopper” version of the .455 Webley revolver cartridge was also introduced, featuring a completely squared-off nose with a deep hemispherical cavity.

But while the term “Dum Dum” would forever be associated with this kind of ammunition, this was not, in fact, the first time expanding bullets had been purposely manufactured. As early as the 1870s, high-velocity “Express” cartridges for big-game hunting had been fitted with hollow points to promote expansion and rapidly take down dangerous animals. Nor was this the first time intentionally-expanding ammunition had been used in warfare; the .577 Snider cartridge, first issued in 1867, had a hollow core and was observed to inflict particularly nasty wounds.

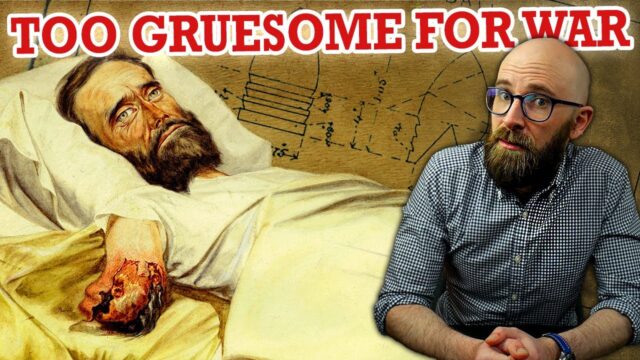

The Mark IV “Dum Dum” cartridge was first used at the September 2, 1898 Battle of Omdurman outside Khartoum, Sudan, in which an Anglo-Egyptian force of 35,000 defeated a Sudanese force of 52,000 under Mahdist leader Abdallahi bin Muhammad. The battle vividly demonstrated the gruesome effectiveness of the new British ammunition, with Major Hugh Mathias of the Royal Army Medical Corps describing the wounds inflicted on one Mahdist soldier:

“He had a bullet wound of the left leg above the knee. The wound entrance was clean cut and very small. The projectile had struck the Femur, just above the internal condyle; the whole of the lower end of this bone, and upper end of the Tibia, were shattered to pieces, the knee joint being completely disorganised.

He had also been wounded in the right shoulder… The whole of the shoulder joint and scapular were shattered to pieces. In neither case was there any sign of a wound of exit.”

Such reports horrified civilians back at home and around the world, who questioned not only the legality of expanding bullets under the 1868 St. Petersburg Declaration but the morality of using such “inhumane” weapons. Now, if it seems odd – if not oxymoronic – to condemn the “humaneness” of weapons of war specifically designed to kill, it is important to understand the particular moral framework upon which the Laws of War as outlined in the Geneva Conventions and St. Petersburg Declaration were built. According to this framework, the point of war was not to kill as many enemy soldiers as possible, but rather to wound only so much as was necessary to render them incapable of fighting – in the language of the time, to place them hors de combat or “out of action”. In the ideal situation, these wounds would be easily treated and quick to heal, allowing the soldiers to live long, healthy lives after the war. Therefore, any weapon which deliberately inflicted more grievous and debilitating wounds than needed to accomplish these ends served only to increase suffering and was unnecessarily cruel and inhumane. Based on these principles, activists pushed for an international ban on expanding bullets. This cause was further spurred on by the work of Professor Paul von Bruns, Surgeon General to the Wūrttemberg Army, who in 1898 published the results of experiments conducted by firing fully-jacketed and hollow-point bullets at wood, clay, human cadavers, and live horses. Von Bruns concluded that any limb struck by a “Dum Dum” projectile would invariably require amputation, and following the publication of his paper the German Congress of Surgeons issued a resolution demanding that expanding projectiles be excluded from “civilized warfare.”

Meanwhile, British military and colonial authorities balked at these protests, arguing that since expanding bullets contained no explosive or fulminating material, they were still perfectly legal under the St. Petersburg declaration. Furthermore, they pointed out that bullets like the Mark IV were, in fact, nothing new; indeed, prior to the introduction of jacketed bullets, all small arms projectiles deformed on impact, inflicting equally gruesome wounds. Thus, the Mark IV was, in a sense, a reversion to older technology. And in any case, such bullets were never intended for “civilized” warfare against other western armies but rather reserved for use against “savage tribes” in the colonies. Finally, the British claimed that the whole debate was nothing more than an anti-British smear organized by Britain’s enemies, pointing out that only the British Mark IV cartridge was being singled out for criticism while the Swiss and Portuguese use of expanding ammunition was ignored.

While most medical professionals pushed for a ban on expanding bullets, others sided with military, with British Surgeon Alexander Ogston questioning the methodology of Von Bruns’s experiments and the very concept of the relative “humaneness” of fully-jacketed bullets:

“[The critics seem to believe that] one who has a limb injured by a fully mantled bullet has before him but a few weeks of pleasant sojourn in bed, while the open-fronded bullets will cost him his limb by amputation, if not worse.”

Nevertheless, on May 18, 1899, a Convention opened in the Hague to hammer out further international laws of war. Attended by representatives of 26 countries – Austria-Hungary, Belgium, Bulgaria, China, Denmark, Germany, France, Greece, Italy, Japan, Luxembourg, Mexico, Montenegro, the Netherlands, the Ottoman Empire, Persia, Portugal, Romania, Serbia, Siam, Spain, Sweden and Norway, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, and the United States – the conference covered a wide range of topics, including the peaceful arbitration of international disputes, the treatment of prisoners of war, and further limitations on the types of weapons allowed in warfare. By the time the Convention concluded on July 29, the attendees had signed three treaties and three declarations: the Convention for the Pacific Settlement of International Disputes, which established a Permanent Court of Arbitration in the Hague; the Convention with Respect to the Laws and Customs of War on Land, which further refined the laws regarding the conduct at war such as the treatment of prisoners and non-combatant civilians; the Convention for the Adaptation to Maritime Warfare, which required belligerents to treat shipwrecked and wounded enemy sailors like prisoners of war on land; the Declaration concerning the Prohibition of the Discharge of Projectiles and Explosives from Balloons or by Other New Analogous Methods; the Declaration concerning the Prohibition of the Use of Projectiles with the Sole Object to Spread Asphyxiating Poisonous Gases; and, finally, Declaration concerning the Prohibition of the Use of Bullets which can Easily Expand or Change their Form inside the Human Body such as Bullets with a Hard Covering which does not Completely Cover the Core, or containing Indentations. While the British delegates – including Major General Ardagh – doggedly argued their case, in the end the anti-Dum Dum crowd won out and all the delegates except the United Kingdom, Portugal, and the United States signed and ratified the declaration.

However, the declaration was non-binding unless signed and ratified, meaning Britain was under no obligation to withdraw its Dum-Dum bullets from service. Nonetheless, when the Second Anglo-Boer War in South Africa broke out in October 1899, the War Office ordered all Mark IV rifle and Mark III pistol ammunition recalled from the battlefield. This was done not in compliance with the Hague Convention, but rather to counter accusations of inhumane warfare practices levelled by the Dutch, French, Germans, and Irish. Officially, no expanding ammunition was used in South Africa, nor during the 1900 Boxer Rebellion in China. However, in 1903, British forces were overwhelmed and annihilated by Somali forces at Gumburru, a defeat partially attributed to the ineffectiveness of the fully-jacketed Mark II cartridge against the Dervish warriors. Consequently, Mark IV Dum-Dums were quickly re-issued to British troops in Somaliland. United States forces also used expanding ammunition during the 1899-1913 Moro Rebellion in the Philippines.

Meanwhile, British arms manufacturers began looking for a bullet design that would have the same stopping power as the Mark IV while still complying with the 1899 Hague Convention. A Mark VI bullet with a thinner jacket was experimented with in 1904, but its performance proved unsatisfactory. Then, in 1905, Germany shook the arms world by introducing the 7.92×57 millimetres Mauser cartridge, which featured a lightweight pointed or “Spitzer” bullet that travelled at a blistering 884 metres per second. So fast were these bullets that, despite not expanding or deforming, they inflicted disproportionately large, gaping wounds via a phenomenon known as hydrostatic shock. At first the British tried to copy the German design, but neither the .303 cartridge case nor the action of the new Lee-Enfield rifle were strong enough to withstand the required pressures. Instead, in 1910 they unveiled the Mark VII bullet, which featured a lightweight aluminium tip ahead of a conventional lead core, all covered in a full metal jacket. This design moved the centre of gravity to the rear of the bullet, meaning that as soon as it struck its target, it would begin tumbling end-over-end – tearing a wound channel just as big – if not bigger – than the Mark IV Dum-Dum. But, because the bullet didn’t actually expand or explode, it remained perfectly legal under the 1899 Hague Convention and its 1907 follow-up. Ah, technical correctness: the best kind of correctness!

Today, it remains illegal to use expanding ammunition in warfare, though projectiles that wound through tumbling or hydrostatic shock are near-universal. And outside the military, expanding bullets are widely used by hunters and law enforcement for the same reason they were originally developed: for quickly and effectively taking down targets. Indeed, it is notable that of the three declarations of the 1899 Hague Convention, the third banning expanding ammunition should be the most universally obeyed. For less than fifteen years later, the prohibitions against air-dropped projectiles and poison gas – arguably more horrific weapons than Dum-Dum bullets – would be violated in spectacular fashion in the bloody quagmire of the First World War.

Expand for References

Hogg, Ian, The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Ammunition, Chartwell Books, Inc, Secaucus, New Jersey, 1985

Reimer, Terry, Wounds, Ammunition, and Amputation, National Museum of Civil War Medicine, November 9, 2007, https://www.civilwarmed.org/surgeons-call/amputation1/

Minie Ball: the Civil War Bullet That Changed History, HistoryNet, https://www.historynet.com/minie-ball/

Hamilton, John, Gardiner’s Explosive Musket Shell, American Society of Firearms Collectors, https://americansocietyofarmscollectors.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Gardiners-explosive-musket-shell-Civil-War-Hamilton-v120.pdf

Declaration Renouncing the Use, in Time of War, of Explosive Projectiles Under 400 Grammes Weight, December 11, 1868, International Humanitarian Law Databases, https://ihl-databases.icrc.org/en/ihl-treaties/st-petersburg-decl-1868/declaration?activeTab=undefined

Garibian, Taline, Pain, Medicine, and the Monitoring of War Violence: the Case of Rifle Bullets (1868-1918), Medical History, April 2022, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9272538/

Abbenhuis, Maartje, Humanitarian Bullets and Man-Killers: Revisiting the History of Arms Regulation in the Late Nineteenth Century, International Review of the Red Cross, November 2022, https://international-review.icrc.org/articles/humanitarian-bullets-and-man-killers-920#footnote68_khcz4nd

Haley, Charlie, .303 Rifle, Digger History, https://web.archive.org/web/20100817090330/http://www.diggerhistory.info/pages-weapons/303.htm#.303

The post What the Heck is a “Dum-Dum” Bullet Anyway? appeared first on Today I Found Out.