Unveiled in Israel: The Clandestine 2,900-Year-Old Workshop Behind the Legendary Tyrian Purple Dye

“We therefore assume it was the main supplier of dyed wool for elite and royal weaving centers across the region — Philistia, Israel, Phoenicia, Moab, Edom, Damascus, Cyprus, etc,” Shalvi told All That’s Interesting. “The site was probably a key economic hub for the Kingdom of Israel and later the Assyrian Empire, both of which ruled the area at different times. Its repeated destruction and subsequent rapid reconstruction suggest a strong motivation to keep it functioning.”

Indeed, from the Israelites and the Phoenicians to the Assyrians and the Romans, the treasured dye known as Tyrian purple was a mainstay in the ancient world.

The Colorful History Of Tyrian Purple, History’s Most Expensive And Prized Dye

The history of Tyrian purple (also known as Mycenaean purple) possibly began as early as the 16th century B.C.E., when it was first produced in the Phoenician city of Tyre (in present-day Lebanon). Phoenician mythology states that the god Melqart discovered the dye after his dog bit a sea snail during a walk on the beach, and emerged from the encounter with a purple snout.

Public DomainThe Phoenician myth was adapted by the Greeks, who claimed that Hercules discovered the dye while walking with his dog.

Tyrian purple was painstakingly produced by gathering sea snails (Hexaplex trunculus, Bolinus brandaris, or Stramonita haemastoma). Ancient people either crushed the snails or extracted their glands, which were then salted, fermented, cooked, and reduced.

“It is considered of the best quality when it has exactly the colour of clotted blood, and is of a blackish hue to the sight,” Roman writer Pliny the Elder once wrote of Tyrian purple, “but of a shining appearance when held up to the light; hence it is that we find Homer speaking of ‘purple blood.’”

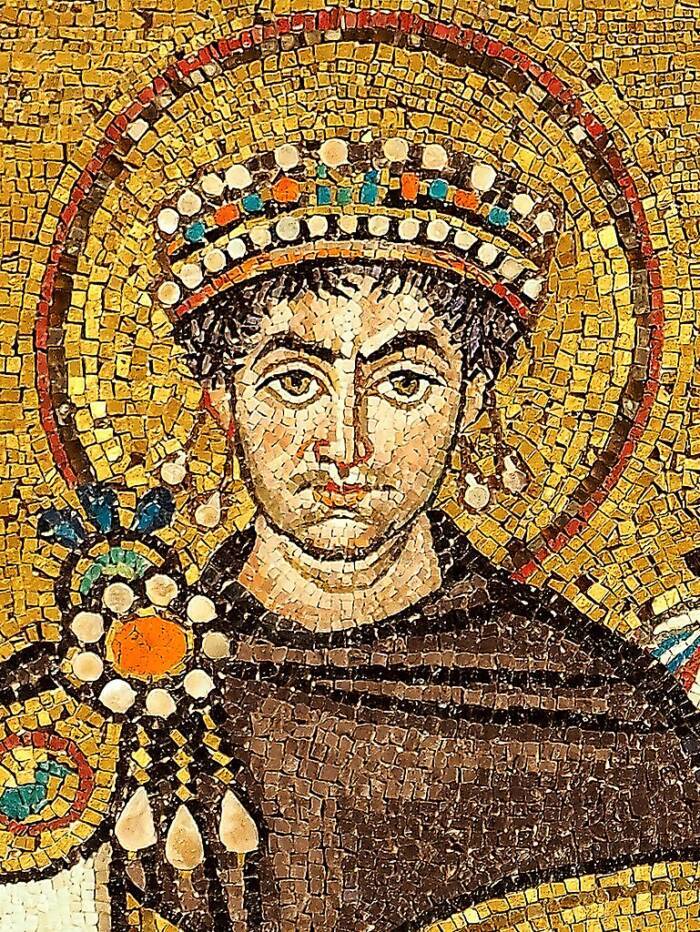

This dye was highly coveted by those who could afford it — in the fourth century C.E. one pound of Tyrian purple was worth three times as much as gold — and it swiftly became the color of ancient elites. And the elites guarded their color with passion. Indeed, the Roman emperor Caligula grew so enraged when the king of Mauretania wore purple to meet with him that Caligula had the king killed.

But as time passed, the passion for Tyrian purple faded. At Tel Shiqmona, the invading Babylonians didn’t bother to restore the site after military campaigns left it in ruins around 600 B.C.E. The factory’s production ceased, and, eventually, even the exact method of creating the dye became lost to the ages.

Petar Milošević/Wikimedia CommonsA sixth-century mosaic of Emperor Justinian I, wearing Tyrian purple.

As such, the purple dye factory discovered in Israel belongs to a long and ancient tradition. In antiquity, there were few things as coveted as Tyrian purple. And for hundreds of years, workers in Tel Shiqmona toiled to make it, collecting snails, crushing their shells, and fermenting their glands until they had produced a dye the color of “clotted blood,” a rich hue that we can still see on ancient artifacts nearly three millennia later.

After reading about the Tyrian purple factory that was unearthed along the coast of northern Israel, discover the story of Egyptian blue, the precious dye used in everything from mummy portraits to Renaissance masterpieces. Then, learn about the discovery of Tyrian purple in England in 2024.

Auto Amazon Links: No products found.