Why Did Ancient Egyptians Shatter Pharaoh Hatshepsut’s Statues? The Chilling Truth Revealed

So, here’s a wild thought: what if those infamous smashed statues of Queen Hatshepsut aren’t simply the result of some epic sibling rivalry or a royal “I hate you” tantrum? For nearly a century, history textbooks and archaeologists alike have pointed a suspicious finger at her stepson, Thutmose III, blaming him for wrecking her statues because, well, she was a rare female pharaoh and, apparently, hard to love. But hold your horses—new research is flipping that dusty old script on its head. It turns out, the broken statues might not be about spite or scandal at all, but about mystical “deactivation ceremonies” to snuff out their supernatural mojo… and maybe some good old-fashioned recycling for building materials later on. Intrigued yet? Because I sure am. Ready to dive into a tale of pharaohs, power plays, and puzzling stone busts? You’re about to discover that sometimes, history isn’t just rewritten—it’s cracked into pieces and put back together tellin’ a very different story. LEARN MORE

For the last century, experts had largely assumed that many statues of Hatshepsut were broken during antiquity because she was a rare female ruler and because her stepson and successor, Thutmose III, despised her and wanted to tarnish her legacy.

Harry Burton/The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Department of Egyptian Art ArchivesFragments of a limestone Hatshepsut statue circa 1929.

When archaeologists began excavating the Deir el-Bahri necropolis near Luxor, Egypt in the 1920s, they discovered a number of smashed and destroyed statues of the same ancient pharaoh.

This pharaoh, Hatshepsut, was one of the few women to serve as the ruler of ancient Egypt. Ever since these broken statues were found, archaeologists have largely believed that they had been violently destroyed on the orders of her stepson and successor, Thutmose III, because he despised her.

However, a new study published in the journal Antiquity suggests that personal vengeance against Hatshepsut may not have been the prime motivator for this widespread destruction of her statues. Instead, the statues may have been damaged as part of a ritual to deactivate their supposed supernatural power, and later to repurpose them for building materials as well.

Hatshepsut’s Unconventional Rise To The Throne And The Myth Of Her Vengeful Stepson

Hatsheptsut ruled Egypt from approximately 1473 B.C.E. until her death in 1458 B.C.E., during the 18th Dynasty of the New Kingdom period.

Unlike her male counterparts, Hatshepsut’s rise to pharaoh status was more complicated. She had been married to Pharaoh Thutmose II, and when he died in 1479 B.C.E., the throne went to his son Thutmose III, who he had with a different woman.

Thutmose III was a baby when his father died and could not rule. So, Hatshepsut acted as regent for the small child. But not long after, Hatshepsut declared herself pharaoh (making her, alongside the likes of Nefertiti, one of ancient Egypt’s rare female rulers) and reigned for the next 22 years.

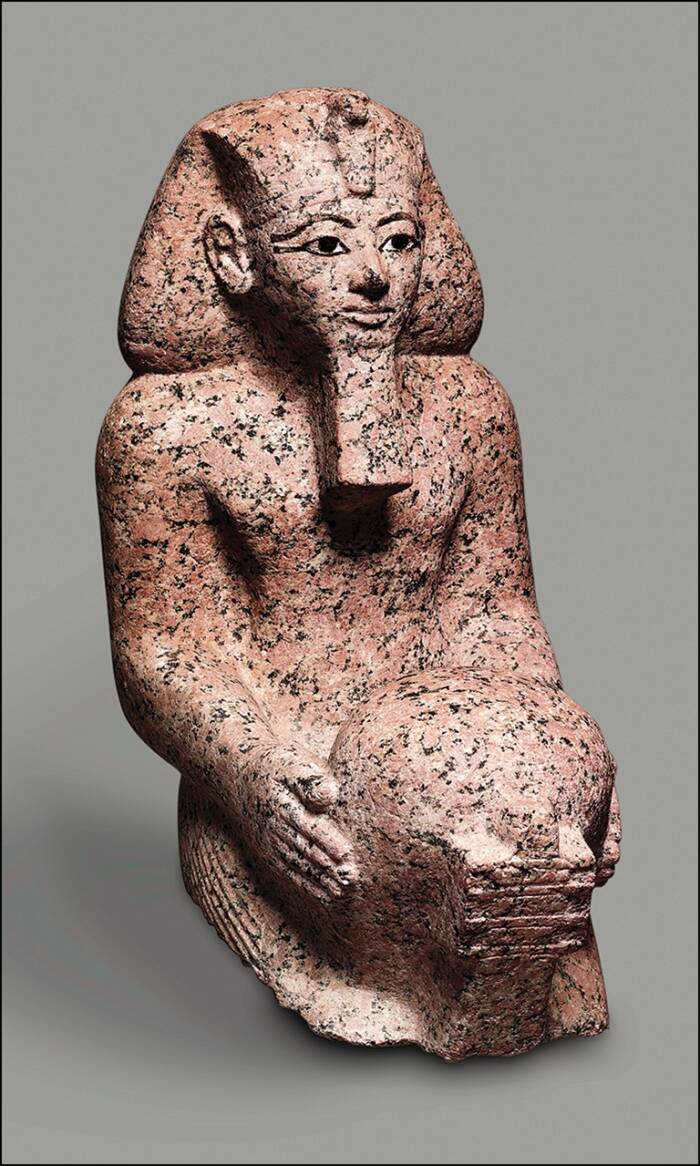

The Metropolitan Museum of ArtSome of Hatshepsut’s statues remain intact.

Since the discovery of her shattered and broken statues at Deir el-Bahri, archaeologists thought this was the result of a hateful smear campaign driven by Thutmose III against his stepmother once he took the throne.

However, Egyptology researcher Jun Yi Wong believes there is a deeper reason behind the damage, one that symbolizes the “deactivation” of a pharaoh’s power even after death.

“While the ‘shattered visage’ of Hatshepsut has come to dominate the popular perception, such an image does not reflect the treatment of her statuary to its full extent,” Wong explained in a statement from Antiquity. “Many of her statues survive in relatively good condition, with their faces virtually intact.”

Why Hatshepsut Statues May Have Been Broken To Deactivate Their Supposed Supernatural Powers

There is still evidence to suggest that Thutmose III did wage some posthumous vendetta against his step-mother. Near the end of his 33-year rule, he did remove her name from the list of kings and he did order that her statues to be broken.

But in reviewing the unpublished notes from the original excavation of the statues, Wong found out that not all of the damage was dated to the time of Thutmose III’s reign.

The damage can be separated into different phases, the first phase being the damage caused by Thutmose III. The rest of the damage occurred later, likely by people wanting to collect repurposed building materials.

“Once you take away all this later damage, you find that the destruction caused by Thutmose III was limited and very methodical—the statues were broken across specific weak points, in line with what is often described as the ‘deactivation’ of Egyptian statues,” Wong explained.

The Metropolitan Museum of ArtA bust of Hatshepsut that has been partially restored.

This practice of deactivating previous pharaohs’ statues was not a rare one in ancient Egypt. Because the people considered pharaoh statues to be a kind of living entity, the statues would be severed at their weak points to snuff out their power. The damage from many of Hatshepsut’s statues falls in line with this methodical destruction.